problem

stringlengths 2

1.73k

| answer

stringlengths 1

313

| solution

stringlengths 3

9.24k

| difficulty

float64 1

10

|

|---|---|---|---|

6. In the Kingdom of Mathematics, the denominations of banknotes in circulation are 1 yuan, 5 yuan, 10 yuan, 20 yuan, 50 yuan, and 100 yuan. One day, two customers each bought a chocolate bar worth 15 yuan at the same grocery store. One of them paid with two 10-yuan banknotes, while the other paid with a 20-yuan and a 5-yuan banknote. When settling the accounts, the boss only needed to give one 10-yuan banknote from the first person to the second person, and then give the 5-yuan banknote from the second person to the first person. One day, two more customers came to buy chewing gum of the same price, and a similar situation occurred as before, where both paid more than the price. The boss only needed to give part of the first person's payment to the second person, and then give part of the second person's payment to the first person. Therefore, ( ) is a possible price for the chewing gum.

(A) 2 yuan

(B) 6 yuan

(C) 7 yuan

(D) 8 yuan

|

8

|

【Answer】D

【Analysis】Considering the four cases respectively, when the gum costs 8 yuan, one person pays 10 yuan (2 five-yuan notes), and another person pays 13 yuan (1 ten-yuan note, 3 one-yuan notes), the first person's 1 five-yuan note can be given as change to the second person, and the second person's 2 one-yuan notes can be given as change to the first person, thus completing the change. The other cases do not meet the requirements of the problem, so the answer is D.

| 4.67

|

4. Triples of natural numbers $\left(a_{i}, b_{i}, c_{i}\right)$, where $i=1,2, \ldots, n$ satisfy the following conditions:

1) $a_{i}+b_{i}+c_{i}=2017$ for all $i=1,2, \ldots, n$;

2) if $i \neq j$, then $a_{i} \neq a_{j}, b_{i} \neq b_{j}$ and $c_{i} \neq c_{j}$. What is the maximum possible value of $n$? (M. Popov)

|

1343

|

Answer: 1343.

Solution: Note that

$$

\sum_{i=1}^{n} a_{i} \geqslant \sum_{i=1}^{n} i=\frac{n(n+1)}{2} .

$$

A similar inequality is written for the sums $b_{i}$ and $c_{i}$. Adding the three obtained inequalities, we get

$$

\begin{gathered}

3 \cdot \frac{n(n+1)}{2} \leqslant \sum_{i=1}^{n} a_{i}+\sum_{i=1}^{n} b_{i}+\sum_{i=1}^{n} c_{i}= \\

=\sum_{i=1}^{n}\left(a_{i}+b_{i}+c_{i}\right)=2017 n .

\end{gathered}

$$

Thus, we obtain the upper bound

$$

\frac{3(n+1)}{2} \leqslant 2017 \Longrightarrow n \leqslant 1343

$$

Now let's provide an example where this bound is achieved ( $n=1343$ )

| $a_{i}$ | $b_{i}$ | $c_{i}$ |

| :---: | :---: | :---: |

| 1 | 672 | 1344 |

| 2 | 673 | 1342 |

| $\vdots$ | $\vdots$ | $\vdots$ |

| 672 | 1343 | 2 |

| 673 | 1 | 1343 |

| 674 | 2 | 1341 |

| $\vdots$ | $\vdots$ | $\vdots$ |

| 1343 | 671 | 3 |

| 4.67

|

5. What is the maximum number of rooks that can be placed on the cells of a $300 \times 300$ board so that each rook attacks no more than one other rook? (A rook attacks all cells it can reach according to chess rules, without passing through other pieces.)

#

|

400

|

# Answer: 400

First solution. We will prove that no more than 400 rooks can be placed on the board. In each row or column, there are no more than two rooks; otherwise, the rook that is not at the edge will attack at least two other rooks. Suppose there are $k$ columns with two rooks each. Consider one such pair. They attack each other, so there are no rooks in the rows where they are located. Thus, rooks can only be in $300-2k$ rows. Since there are no more than two rooks in each of these rows, the total number of rooks is no more than $2(300-2k) + 2k = 600 - 2k$. On the other hand, in $k$ columns, there are two rooks each, and in the remaining $300-k$ columns, there is no more than one rook, so the total number of rooks is no more than $(300-k) + 2k = 300 + k$. Therefore, the total number of rooks is no more than $\frac{1}{3}((600-2k) + 2(300+k)) = 400$.

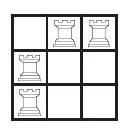

Next, we will show how to place 400 rooks. On a $3 \times 3$ board, 4 rooks can be placed as shown in the figure, and then 100 such squares can be placed along the diagonal.

Second solution. On the board, there can be rooks that do not attack any other rooks, as well as pairs of rooks that attack each other. Let there be $k$ single rooks and $n$ pairs of rooks that attack each other. Then the total number of rooks on the board is $k + 2n$. We will count the total number of occupied rows and columns (for convenience, we will call them lines). Each single rook occupies its own row and its own column, i.e., two lines. Each pair of rooks occupies three lines. Therefore, the total number of lines occupied is $2k + 3n$. Thus, $2k + 3n \leq 600$. Therefore, $k + 2n = \frac{2}{3}(2k + 3n) - \frac{k}{3} \leq \frac{2}{3}(2k + 3n) \leq \frac{2}{3} \cdot 600 = 400$.

The example of placement is the same as in the first solution.

| 5

|

4. A kilo of sausages was placed on a straight line between a dog in a kennel and a cat. The animals simultaneously rushed to the sausages. The cat runs twice as fast as the dog, but eats twice as slowly. Upon reaching the sausages, both ate without fighting and ate an equal amount. It is known that the cat could eat all the sausages in one minute and also run from the starting point to the dog's kennel in one minute. To whom were the sausages placed closer, and by how many times?

|

1.4

|

Answer: 1.4 times closer to the dog than to the cat.

## Solution:

Let $v$ be the running speed of the dog, $u$ be the eating speed of the cat, and the volume of sausages eaten by each animal be 1.

Then, $2 v$ is the running speed of the cat, and $2 u$ is the eating speed of the dog.

Let the distance from the cat to the sausages be $x$, and the distance from the dog's kennel to the sausages be $-y$.

The total time from the start of movement to the end of eating sausages is the same for both the cat and the dog, i.e., $x / 2 v + 1 / u = y / v + 1 / 2 u$.

According to the condition, we have: $2 / u = (x + y) / 2 v$.

Substituting $1 / u$ and $1 / 2 u$ in the first equation with $(x + y) / 4 v$ and $(x + y) / 8 v$ respectively, derived from the second equality,

we get $x / 2 v + (x + y) / 4 v = y / v + (x + y) / 8 v$.

Multiplying by $8 v$, we have: $4 x + 2(x + y) = 8 y + (x + y)$.

Combining like terms, we finally get: $5 x = 7 y$, hence the answer.

## Instructions for Checking:

Answer without justification but with verification - 2 points.

Answer without verification - 1 point.

| 2

|

Compute the smallest positive integer that does not appear in any problem statement on any round at HMMT November 2023.

|

22

|

The number 22 does not appear on any round. On the other hand, the numbers 1 through 21 appear as follows. \begin{tabular}{c|c|c} Number & Round & Problem \\ \hline 1 & Guts & 21 \\ 2 & Guts & 13 \\ 3 & Guts & 17 \\ 4 & Guts & 13 \\ 5 & Guts & 14 \\ 6 & Guts & 2 \\ 7 & Guts & 10 \\ 8 & Guts & 13 \\ 9 & Guts & 28 \\ 10 & Guts & 10 \\ 11 & General & 3 \\ 12 & Guts & 32 \\ 13 & Theme & 8 \\ 14 & Guts & 19 \\ 15 & Guts & 17 \\ 16 & Guts & 30 \\ 17 & Guts & 20 \\ 18 & Guts & 2 \\ 19 & Guts & 33 \\ 20 & Guts & 3 \\ 21 & Team & 7 \end{tabular}

| 1.6

|

I2.3 Determine the smallest positive integer $\gamma$ such that the equation $\sqrt{x}-\sqrt{\beta \gamma}=4 \sqrt{2}$ has an integer solution in $x$.

|

3

|

$$

\begin{array}{l}

\sqrt{x}-\sqrt{24 \gamma}=4 \sqrt{2} \\

\sqrt{x}=2 \sqrt{6 \gamma}+4 \sqrt{2}

\end{array}

$$

The smallest positive integer $\gamma=3$

| 1.6

|

## Task 1.

If $a_{1}, a_{2}, \ldots, a_{2000}$ is a sequence of 2000 positive real numbers, for how many indices $i \in$ $\{1,2, \ldots, 2000\}$ can the equality

$$

a_{i} a_{i+3}=a_{i} a_{i+1}+a_{i+1} a_{i+2}+a_{i+2} a_{i+3} ?

$$

hold? We consider that $a_{j+2000}=a_{j}$ for $j \in\{1,2,3\}$.

|

999

|

## Solution.

For an index $i$, we say it is good if it satisfies the equality in the problem statement.

Assume there exist two consecutive good indices $i, i+1$. Then we have

$$

\begin{aligned}

a_{i} a_{i+3} & =a_{i} a_{i+1}+a_{i+1} a_{i+2}+a_{i+2} a_{i+3} \\

a_{i+1} a_{i+4} & =a_{i+1} a_{i+2}+a_{i+2} a_{i+3}+a_{i+3} a_{i+4}

\end{aligned}

$$

From the first equality, it follows that $a_{i+1}a_{i+3}$, which is a contradiction. Therefore, there do not exist two consecutive good indices, so the number of good indices is at most 1000.

Furthermore, if index $i$ is good, then $a_{i}>a_{i+2}$. Assume there are 1000 good indices. Then these indices are $i, i+2, i+4, \ldots, i+1998$ for some $i$. However, then we have

$$

a_{i}>a_{i+2}>a_{i+4}>\ldots>a_{i+1998}>a_{i+2000}=a_{i}

$$

which is a contradiction. We conclude that there are at most 999 good indices.

Now we construct an example of a 2000-tuple where the indices $1,3,5, \ldots, 1997$ are good. Let $a_{1}>a_{3}>\ldots>a_{1999}$ be arbitrary positive real numbers, and let $a_{2}$ be any positive real number. Assume we have defined the numbers $a_{2}, a_{4}, \ldots, a_{2 i}$ for some $i \in\{1, \ldots, 999\}$.

We recursively define $a_{2 i+2}$ so that $2 i-1$ is a good index, i.e., $a_{2 i+2}$ is defined as a number such that $a_{2 i-1} a_{2 i+2}=a_{2 i-1} a_{2 i}+a_{2 i} a_{2 i+1}+a_{2 i+1} a_{2 i+2}$, or

$$

a_{2 i+2}=a_{2 i} \cdot \frac{a_{2 i-1}+a_{2 i+1}}{a_{2 i-1}-a_{2 i+1}}

$$

It is easy to see that $a_{2 i+2}$ is a well-defined positive real number, since $a_{2 i-1}>a_{2 i+1}$. Thus, the 2000-tuple $(a_{1}, a_{2}, \ldots, a_{2000})$ defined in this way has 999 good indices.

Note: Of course, it is also possible to explicitly construct a sequence with 999 good indices. For example, the sequence

$$

2^{0}, 3^{0}, 2^{-1}, 3^{1}, 2^{-2}, 3^{2}, \ldots, 2^{-999}, 3^{999}

$$

| 5.5

|

13.1. [7-8.7 (20 points), 9.8 (15 points), 10.8 (20 points)] There is a rotating round table with 16 sectors, on which numbers $0,1,2, \ldots, 7,8,7,6, \ldots, 2,1$ are written in a circle. 16 players are sitting around the table, numbered in order. After each rotation of the table, each player receives as many points as the number written on the sector they end up in after the table stops. It turned out that after 13 rotations of the table, player number 5 scored a total of 72 points, and player number 9 scored a total of 84 points. How many points did player number 1 score?

|

20

|

Answer: 20.

Solution. Players No. 5 and No. 9 together scored $72+84=156=12 \cdot 13$ points. In one spin, they can together score no more than 12 points. Therefore, in each of the 13 spins, they together scored 12 points. Note that the 12 points they score can be one of the sums $8+4, 7+5$, $6+6, 5+7$ or $4+8$, when the sector 8 is in front of one of them or between them, i.e., in front of one of the players with numbers $6, 7, 8$. In each of these five cases, player No. 1 scores respectively $4, 3, 2, 1$ or 0 points. This can be expressed by the formula $x_{1}=\frac{x_{5}-x_{9}}{2}+2$, where $x_{n}$ is the number of points scored by the player with number $n$ in this spin. Then the number of points scored by player No. 1 after 13 spins is $\frac{72-84}{2}+2 \cdot 13=20$.

| 5.75

|

7. (10 points) The last 8 digits of $11 \times 101 \times 1001 \times 10001 \times 1000001 \times 111$ are

|

87654321

|

【Analysis】By applying the commutative and associative laws of multiplication to integrate $11 \times 101 \times 1001 \times 10001 \times 1000001 \times 111$, then organize it into $11111111 \times 111111111111$, we can derive that the last 8 digits of $11 \times 101 \times 1001 \times 10001 \times 1000001 \times 111$ are 87654321; based on this, solve the problem.

【Solution】Solution: $11 \times 101 \times 1001 \times 10001 \times 1000001 \times 111$

$$

\begin{array}{l}

=(11 \times 101) \times 1001 \times 10001 \times 1000001 \times 111 \\

=(1111 \times 10001) \times 1001 \times 1000001 \times 111 \\

=11111111 \times 111111 \times 1000001 \\

=11111111 \times 111111111111 ;

\end{array}

$$

Since $1111 \times 1111=1234321, 1111 \times 111111=123444321$,

$$

111111 \times 111111=12345654321, \quad 111111 \times 11111111=1234566654321,

$$

Therefore: $11111111 \times 111111111111=1234567888887654321$,

So the last 8 digits of $11 \times 101 \times 1001 \times 10001 \times 1000001 \times 111$ are 87654321; Answer: The last 8 digits of $11 \times 101 \times 1001 \times 10001 \times 1000001 \times 111$ are 87654321. The answer is: 87654321.

| 4

|

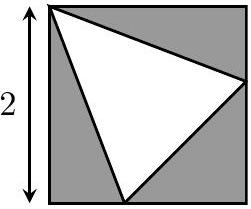

As shown in the figure, $\triangle A B C$ is an isosceles right triangle, $A B=28 \mathrm{~cm}$. A semicircle is drawn with $B C$ as the diameter, and point $D$ is the midpoint of the semicircle arc. Try to find the area of the shaded part. (Take $\pi=\frac{22}{7}$.)

|

252 \text{ cm}^2

|

Geometry, cleverly finding area, cutting and supplementing.

(Method 1)

Take the midpoint $E$ of $B C$, connect $D E$; connect $B D$;

$S_{\triangle A B D}=A B \times B E \div 2=28 \times 14 \div 2=196$ square centimeters;

$S_{\text {sector } B E D}=\frac{1}{4} \times \pi \times B E^{2}=\frac{1}{4} \times \pi \times 14^{2}=49 \pi$ square centimeters;

$S_{\triangle B E D}=B E \times D E \div 2=14 \times 14 \div 2=98$ square centimeters;

$S_{\text {shape } B D}=S_{\text {sector } B E D}-S_{\triangle B E D}=49 \pi-98$ square centimeters;

$S_{\text {shaded }}=S_{\triangle A B D}+S_{\text {shape } B D}=196+(49 \pi-98)=49 \pi+98=49 \times \frac{22}{7}+98=252$ square centimeters.

(Method 2)

Take the midpoint $E$ of $B C$, connect $D E$; connect $B D$;

Since $\triangle A B C$ and $\triangle B D E$ are both isosceles right triangles;

Therefore, $\angle A C B=\angle D B E=45^{\circ}$;

Therefore, $A C / / B D$;

Therefore, $S_{\triangle A B D}=S_{\triangle C B D}$;

$S_{\text {sector } B E D}=\frac{1}{4} \times \pi \times B E^{2}=\frac{1}{4} \times \pi \times 14^{2}=49 \pi$ square centimeters;

$S_{\triangle C E D}=C E \times D E \div 2=14 \times 14 \div 2=98$ square centimeters;

$S_{\text {shaded }}=S_{\text {sector } B E D}+S_{\triangle C E D}=49 \pi+98=49 \times \frac{22}{7}+98=252$ square centimeters.

| 3

|

14. (12 points) Use 36 solid rectangular prisms of size $3 \times 2 \times 1$ to form a large cube of size $6 \times 6 \times 6$. Among all possible arrangements, the maximum number of small rectangular prisms that can be seen from a point outside the large cube is $\qquad$.

|

\documentclass{article}

\usepackage{amsmath}

\usepackage{amssymb}

\begin{document}

31

\end{document}

|

【Answer】Solution: As shown in the figure,

To see the maximum number from the outside, it is necessary to make the rectangles seen from the outside as "deeply" inside the square as possible, the result is as follows: a total of $6 \times 3+3 \times 4+3 \times 1+1=31$ (pieces). Therefore, the answer is: 31.

| 4

|

11. (3 points) There are 20 points below, with each adjacent pair of points being equidistant. By connecting four points with straight lines, you can form a square. Using this method, you can form $\qquad$ squares.

The text above has been translated into English, preserving the original text's line breaks and format.

|

20

|

【Answer】Solution: The number of squares with a side length of 1 unit is 12;

The number of squares with a side length of 2 units is 6;

The number of squares with a side length of 3 units is 2;

The maximum side length is 3 units, any larger and it would not form a square;

In total, there are squares: $12+6+2=20$ (squares).

Answer: A total of 20 squares can be obtained.

Therefore, the answer is: 20.

| 1

|

## Task B-2.1.

For which values of the real parameter $m$ does the inequality $\left(\frac{x_{1}}{x_{2}}\right)^{2}+\left(\frac{x_{2}}{x_{1}}\right)^{2}<47$ hold if $x_{1}$ and $x_{2}$ are the solutions of the equation $x^{2}-\left(2^{m-1}-5\right) x+1=0$?

|

m \in (2,4)

|

## Solution.

For the solutions of the equation $x^{2}-\left(2^{m-1}-5\right) x+1=0$, we have

$$

x_{1}+x_{2}=2^{m-1}-5 \quad \text{and} \quad x_{1} x_{2}=1

$$

Therefore,

$$

\begin{aligned}

\left(\frac{x_{1}}{x_{2}}\right)^{2}+\left(\frac{x_{2}}{x_{1}}\right)^{2} & =\frac{x_{1}^{4}+x_{2}^{4}}{x_{1}^{2} x_{2}^{2}}=\frac{\left(x_{1}^{2}+x_{2}^{2}\right)^{2}-2 x_{1}^{2} x_{2}^{2}}{x_{1}^{2} x_{2}^{2}} \\

& =\frac{\left(\left(x_{1}+x_{2}\right)^{2}-2 x_{1} x_{2}\right)^{2}-2\left(x_{1} x_{2}\right)^{2}}{\left(x_{1} x_{2}\right)^{2}} \\

& =\frac{\left(\left(2^{m-1}-5\right)^{2}-2\right)^{2}-2 \cdot 1^{2}}{1^{2}}=\left(\left(2^{m-1}-5\right)^{2}-2\right)^{2}-2

\end{aligned}

$$

The given condition is equivalent to

$$

\begin{array}{ll}

& \left(\left(2^{m-1}-5\right)^{2}-2\right)^{2}-2<47 \\

\Leftrightarrow & \left(\left(2^{m-1}-5\right)^{2}-2\right)^{2}<49 \\

\Leftrightarrow & \left|\left(2^{m-1}-5\right)^{2}-2\right|<7 \\

\Leftrightarrow & -7<\left(2^{m-1}-5\right)^{2}-2<7 \\

\Leftrightarrow & -5<\left(2^{m-1}-5\right)^{2}<9

\end{array}

$$

The inequality $-5<\left(2^{m-1}-5\right)^{2}$ holds for all real numbers $m$, and the inequality $\left(2^{m-1}-5\right)^{2}<9$ is equivalent to $-3<2^{m-1}-5<3$ or $2<2^{m-1}<8$, from which we get $1<m-1<3$. Finally, the desired values of the parameter $m$ are $m \in (2,4)$.

| 3.33

|

The elements of the sequence $\mathrm{Az}\left(x_{n}\right)$ are positive real numbers, and for every positive integer $n$,

$$

2\left(x_{1}+x_{2}+\ldots+x_{n}\right)^{4}=\left(x_{1}^{5}+x_{2}^{5}+\ldots+x_{n}^{5}\right)+\left(x_{1}^{7}+x_{2}^{7}+\ldots+x_{n}^{7}\right)

$$

Determine the elements of the sequence.

|

x_n = n

|

The elements of the sequence $\left(x_{n}\right)$ are positive real numbers, and for every positive integer $n$,

$$

2\left(x_{1}+x_{2}+\ldots+x_{n}\right)^{4}=\left(x_{1}^{5}+x_{2}^{5}+\ldots+x_{n}^{5}\right)+\left(x_{1}^{7}+x_{2}^{7}+\ldots+x_{n}^{7}\right)

$$

Determine the elements of the sequence.

Solution. We will prove by induction that $x_{n}=n$ for every positive integer $n$. For $n=1$, the equation is:

$$

2 x_{1}^{4}=x_{1}^{5}+x_{1}^{7}

$$

Rearranging and factoring:

$$

x_{1}^{4}\left(x_{1}^{2}+x_{1}+2\right)\left(x_{1}-1\right)=0

$$

The only positive real root of this equation is 1.

Assume that $k>1$, and that we have repeated this assertion for $n=1,2, \ldots,(k-1)$, i.e., that

$$

x_{1}=1, x_{2}=2, \ldots, x_{k-1}=k-1

$$

is the unique positive real solution of the defining equation of the sequence when $n=k-1$. We will show that for $n=k$, (1) has a unique solution: $x_{k}=k$.

Write down the $k$-th and $(k-1)$-th equations, and subtract the latter, using the identity $1+2+\ldots+(k-1)=\frac{k(k-1)}{2}$:

$$

\begin{gathered}

2\left(1+2+\ldots+(k-1)+x_{k}\right)^{4}=\left(1^{5}+2^{5}+\ldots+(k-1)^{5}+x_{k}^{5}\right)+\left(1^{7}+2^{7}+\ldots+(k-1)^{7}+x_{k}^{7}\right) \\

2(1+2+\ldots+(k-1))^{4}=\left(1^{5}+2^{5}+\ldots+(k-1)^{5}\right)+\left(1^{7}+2^{7}+\ldots+(k-1)^{7}\right) \\

2\left(\frac{k(k-1)}{2}+x_{k}\right)^{4}-2\left(\frac{k(k-1)}{2}\right)^{4}=x_{k}^{5}+x_{k}^{7}

\end{gathered}

$$

Perform the exponentiations and rearrange the equation:

$$

x_{k}^{7}+x_{k}^{5}-2 x_{k}^{4}-4 k(k-1) x_{k}^{3}-3 k^{2}(k-1)^{2} x_{k}^{2}-k^{3}(k-1)^{3} x_{k}=0

$$

We can divide by $x_{k}$, since it is positive; rearranging the parentheses:

$$

x_{k}^{6}+x_{k}^{4}-2 x_{k}^{3}-\left(4 k^{2}-4 k\right) x_{k}^{2}-\left(3 k^{4}-6 k^{3}+3 k^{2}\right) x_{k}-\left(k^{6}-3 k^{5}+3 k^{4}-k^{3}\right)=0

$$

It can be verified by substitution that $x_{k}=k$ is a solution. Factor out the $\left(x_{k}-k\right)$ root:

$$

\left(x_{k}-k\right)\left(x_{k}^{5}+k x_{k}^{4}+\left(k^{2}+1\right) x_{k}^{3}+\left(k^{3}+k-2\right) x_{k}^{2}+\left(k^{4}-3 k^{2}+2 k\right) x_{k}+\left(k^{5}-3 k^{4}+3 k^{3}-k^{2}\right)\right)=0

$$

We claim that every coefficient in the second factor is positive. It is sufficient to prove this from the fourth term onwards. Indeed,

$$

\begin{aligned}

& k^{3}+k-2 \geq k^{3}+2-2>0 \\

& k^{4}-3 k^{2}+2 k>k^{4}-4 k^{2}+4=\left(k^{2}-2\right)^{2} \geq 0 \text { and } \\

& k^{5}-3 k^{4}-3 k^{3}-k^{2}=k^{2}(k-1)^{3}>0

\end{aligned}

$$

Therefore, since $x_{k}>0$, the second factor is always positive, and the only positive root of the equation is: $x_{k}=k$.

This completes the proof of our statement.

| 5

|

Alice and the Cheshire Cat play a game. At each step, Alice either (1) gives the cat a penny, which causes the cat to change the number of (magic) beans that Alice has from $n$ to $5n$ or (2) gives the cat a nickel, which causes the cat to give Alice another bean. Alice wins (and the cat disappears) as soon as the number of beans Alice has is greater than 2008 and has last two digits 42. What is the minimum number of cents Alice can spend to win the game, assuming she starts with 0 beans?

|

35

|

Consider the number of beans Alice has in base 5. Note that $2008=31013_{5}, 42=132_{5}$, and $100=400_{5}$. Now, suppose Alice has $d_{k} \cdots d_{2} d_{1}$ beans when she wins; the conditions for winning mean that these digits must satisfy $d_{2} d_{1}=32, d_{k} \cdots d_{3} \geq 310$, and $d_{k} \cdots d_{3}=4i+1$ for some $i$. To gain these $d_{k} \cdots d_{2} d_{1}$ beans, Alice must spend at least $5\left(d_{1}+d_{2}+\cdots+d_{k}\right)+k-1$ cents (5 cents to get each bean in the "units digit" and $k-1$ cents to promote all the beans). We now must have $k \geq 5$ because $d_{k} \cdots d_{2} d_{1}>2008$. If $k=5$, then $d_{k} \geq 3$ since $d_{k} \cdots d_{3} \geq 3100$; otherwise, we have $d_{k} \geq 1$. Therefore, if $k=5$, we have $5\left(d_{1}+d_{2}+\cdots+d_{k}\right)+k-1 \geq 44>36$; if $k>5$, we have $5\left(d_{1}+d_{2}+\cdots+d_{k}\right)+k-1 \geq 30+k-1 \geq 35$. But we can attain 36 cents by taking $d_{k} \cdots d_{3}=1000$, so this is indeed the minimum.

| 5

|

18. (2 marks) Let $A_{1} A_{2} \cdots A_{2002}$ be a regular 2002-sided polygon. Each vertex $A_{i}$ is associated with a positive integer $a_{i}$ such that the following condition is satisfied: If $j_{1}, j_{2}, \cdots, j_{k}$ are positive integers such that $k<500$ and $A_{j_{1}} A_{j_{2}} \cdots A_{j_{k}}$ is a regular $k$-sided polygon, then the values of $a_{j_{1}}, a_{j_{2}}, \cdots, a_{j_{k}}$ are all different. Find the smallest possible value of $a_{1}+a_{2}+\cdots+a_{2002}$.

(2 分) 設 $A_{1} A_{2} \ldots A_{2002}$ 為正 2002 邊形 0 每一頂點 $A_{i}$ 對應正整數 $a_{i}$ 使下列條件成立:如果 $j_{1}, j_{2}, \cdots, j_{k}$為正整數, $k<500$, 而 $A_{j_{1}} A_{j_{2}} \ldots A_{j_{k}}$ 為正 $k$ 邊形時, 則 $a_{j_{1}}, a_{j_{2}}, \cdots, a_{j_{k}}$ 的值互不相同。求 $a_{1}+a_{2}+\ldots+a_{2002}$的最小可能值。

|

287287

|

18. Since $2002=2 \times 7 \times 11 \times 13$, we can choose certain vertices among the 2002 vertices to form regular 7-, 11-, 13-, $\cdots$ polygons (where the number of sides runs through divisors of 2002 greater than 2 and less than 1001). Since $2002=7 \times 286$, so there are at least 286 different positive integers among the $a_{i}{ }^{\prime} s$. Hence the answer is at least $7 \times(1+2+\cdots+286)=\frac{7 \times 286 \times 287}{2}=287 \times 1001=287287$. Indeed this is possible if we assign the number $\left[\frac{i}{7}\right]+1$ to each $A_{i}$, for $i=1,2, \cdots, 2002$.

| 6.33

|

9.2. For what least natural $n$ do there exist integers $a_{1}, a_{2}, \ldots, a_{n}$ such that the quadratic trinomial

$$

x^{2}-2\left(a_{1}+a_{2}+\ldots+a_{n}\right)^{2} x+\left(a_{1}^{4}+a_{2}^{4}+\ldots+a_{n}^{4}+1\right)

$$

has at least one integer root?

(P. Kozlov)

|

6

|

Answer. For $n=6$.

Solution. For $n=6$, we can set $a_{1}=a_{2}=a_{3}=a_{4}=1$ and $a_{5}=a_{6}=-1$; then the quadratic trinomial from the condition becomes $x^{2}-8 x+7$ and has two integer roots: 1 and 7. It remains to show that this is the smallest possible value of $n$.

Suppose the numbers $a_{1}, a_{2}, \ldots, a_{n}$ satisfy the condition of the problem; then the discriminant of the quadratic trinomial from the condition, divided by 4, must be a perfect square. It is equal to

$$

d=\left(a_{1}+a_{2}+\ldots+a_{n}\right)^{4}-\left(a_{1}^{4}+a_{2}^{4}+\ldots+a_{n}^{4}+1\right)

$$

Then the number $d$ is odd and is a square, so it gives a remainder of 1 when divided by 8.

Rewrite the above equality as

$$

d+1+a_{1}^{4}+a_{2}^{4}+\ldots+a_{n}^{4}=\left(a_{1}+a_{2}+\ldots+a_{n}\right)^{4}

$$

and consider it modulo 8. It is not hard to check that the fourth powers of integers give only remainders 0 and 1 when divided by 8, so the right-hand side of the equality gives a remainder of 0 or 1. The left-hand side, however, is comparable to $1+1+k$, where $k$ is the number of odd numbers among $a_{i}$. Therefore, $n \geqslant k \geqslant 6$.

| 6

|

2. Fifteen numbers are arranged in a circle. The sum of any six consecutive numbers is 50. Petya covered one of the numbers with a card. The two numbers adjacent to the card are 7 and 10. What number is under the card?

|

8

|

Answer: 8.

Solution. Let the number at the $i$-th position be $a_{i}(i=1, \ldots, 15$.) Fix 5 consecutive numbers. The numbers to the left and right of this quintet must match. Therefore, $a_{i}=a_{i+6}$. Let's go in a circle, marking the same numbers:

$$

a_{1}=a_{7}=a_{13}=a_{4}=a_{10}=a_{1} .

$$

Now it is clear that for any $i$, $a_{i}=a_{i+3}$, i.e., the numbers go in the following order:

$$

a, b, c, a, b, c, \ldots, a, b, c

$$

From the condition, it follows that

$$

2(a+b+c)=50

$$

Thus, the sum of any three consecutive numbers is 25. Hence the answer.

Scoring. 12 points for a complete solution.

| 2.2

|

2. (10 points) Five pieces of paper are written with $1$, $2$, $3$, $4$, and $5$, facing up from smallest to largest, stacked in a pile. Now, the 1, 3, and 5 are flipped to their backs, and still placed in their original positions. If the entire stack of paper is split at any one piece of paper into two stacks, and the upper stack is reversed and placed back on the lower stack, or if the entire stack of 5 pieces of paper is reversed, it counts as one "reversal". To transform the above arrangement of five pieces of paper so that they are all facing up, the minimum number of "reversals" required is $\qquad$. (The side with the number is the front)

|

5

|

2. (10 points) Five pieces of paper are written with $1, 2, 3, 4, 5$ respectively, facing upwards from smallest to largest, stacked into one pile. Now, the $1, 3,$ and $5$ are flipped to their backs and placed back in their original positions. If the entire stack is split at any one piece of paper into two stacks, and the upper stack is reversed and placed back on the lower stack, or if the entire stack of 5 pieces of paper is reversed, it counts as one "reversal". To transform the five pieces of paper from the above arrangement to all facing upwards, at least 5 "reversals" are required. (The side with the number is the front side)

【Analysis】First, consider the entire stack of paper as composed of 5 "sub-stacks", which can help determine the change in the number of "sub-stacks" after one reversal, leading to the conclusion.

【Solution】Solution: If we consider the entire stack of paper as being composed of parts that are all in the same direction: "sub-stacks", then the original entire stack of paper consists of 5 sub-stacks.

One "reversal" can only start from one piece of paper, placing the top piece of the upper part next to the top piece of the lower part, with the order in between remaining unchanged. After one reversal, the number of "sub-stacks" can only change in three ways: increase by 1, remain unchanged, or decrease by 1. When the entire stack is reversed, the number of "sub-stacks" does not change.

According to the requirement, to turn the 5 into the front side, there must be one reversal of all 5 pieces of paper, and the sequence of the entire stack remains unchanged. To turn 5 sub-stacks into one sub-stack, at least 4 reversals are required. Therefore, at least 5 reversals are needed.

The following explains that 5 reversals can ensure that all 5 pieces of paper are facing upwards: First, reverse the 1, then reverse 1 and 2 together, then reverse $2, 1, 3$, then reverse $3, 1, 2, 4$, and finally reverse $4, 2, 1, 3, 5$ to make them all face upwards, totaling 5 reversals (this is one of the possible sequences of reversals). Therefore, the answer is: 5.

| 2.25

|

Given two positive integers $n$ and $k$. In the plane, there are $n$ circles ($n \geq 2$) such that each circle intersects every other circle at two points, and all these intersection points are pairwise distinct.

Each intersection point is colored with one of $n$ colors such that each color is used at least once and on each of the circles, the same number $k$ of colors is represented.

Determine all values of $n$ and $k$ for which such a coloring is possible.

|

2 \leq k \leq n \leq 3 \text{ or } 3 \leq k \leq n

|

The answer is: $2 \leq k \leq n \leq 3$ or $3 \leq k \leq n$.

Obviously, $k \leq n$ according to the problem statement, and $k \geq 2$, because for $k=1$ all points would have the same color, while the number $n$ of colors should be $\geq 2$. We number the circles and the colors from 1 to n and denote by $F(i, j)$ the set of colors of the intersection points of circles i and j. $F(i, j)$ contains one or two elements.

Let $k=2$. For $n=2$, $F(1,2)=\{1,2\}$ is an allowed coloring. For $n=3$, $F(1,2)=\{3\}$, $F(2,3)=\{1\}, F(3,1)=\{2\}$ is an example of an allowed coloring. Now let $n \geq 4$. To each of the n circles, we assign the set $\{i, j\}$ of the two colors appearing on it. Each of these sets consists of two elements, and each of the n colors must appear in at least two sets, since each colored point is the intersection of two circles. Therefore, each color appears in exactly two sets. For the circle 1 with the set $\{i, j\}$, there are thus at most two other circles whose color sets contain i or j. Since $n \geq 4$, we always find a circle 2 with the set $\{k, l\}$ and $\{k, l\} \cap\{i, j\}=\{ \}$. The intersection points of circles 1 and 2 are then not allowed to be colored, contradiction!

Now we prove by induction a slightly stronger statement than required: For $n \geq k \geq 3$, there always exists an allowed coloring in which the color i appears on the circle i for all $i=1, \ldots, n$. For the base case, we give an example for $k=n=3$ with $F(1,2)=\{1,2\}$, $F(1,3)=\{1,3\}, F(2,3)=\{2,3\}$ and for $k=3, n>3$ the following example of an allowed coloring with the additional condition:

$F(1,2)=\{1,2\}, F(i, i+1)=\{i\}$ for $1<i<n-1, F(n-1, n)=\{n-2, n-1\}$ and $F(i, j)=\{n\}$ for the remaining pairs $(i, j)$ with $1 \leq i<j \leq n$.

Now assume that the stronger statement is true for some $k \geq 3$, and choose $n \geq k+1$. Since $n-1 \geq k \geq 3$, there exists an allowed coloring with the additional condition for the circles or colors 1,2,..., n-1. Now we color the intersection points of circle n: For each $i=1, \ldots, n-1$, one intersection point of circles i and n is colored with color n. Thus, on each of the circles i with $i=1, \ldots, n-1$, exactly $k+1$ colors appear; among them i and $n$. For $i=1, \ldots, k$, the second intersection point of circles i and n is colored with color i, so that now also on circle $n$ exactly $k+1$ colors lie, namely 1 to $k$ and $n$. All other new intersection points are colored with color n, so that no additional colors appear on any circle. This coloring satisfies all conditions.

| 5

|

[ $\underline{\text { Classical Inequalities (Miscellaneous) })]}$

$$

\sqrt{x_{1}^{2}+\left(1-x_{2}\right)^{2}}+\sqrt{x_{2}^{2}+\left(1-x_{3}\right)^{2}}+\ldots+\sqrt{x_{2 n}^{2}+\left(1-x_{1}\right)^{2}}

$$

|

\frac{n}{\sqrt{2}}

|

According to the inequality between the quadratic mean and the arithmetic mean

$$

\begin{aligned}

& \sqrt{2}\left(\sqrt{x_{1}^{2}+\left(1-x_{2}\right)^{2}}+\sqrt{x_{2}^{2}+\left(1-x_{3}\right)^{2}}+\ldots+\sqrt{x_{n}^{2}+\left(1-x_{1}\right)^{2}}\right) \geq \\

& \geq\left|x_{1}\right|+\left|1-x_{2}\right|+\left|x_{2}\right|+\left|1-x_{3}\right|+\ldots+\left|x_{n}\right|+\left|1-x_{1}\right| \geq x_{1}+1-x_{2}+x_{2}+1-x_{3}+\ldots+x_{n}+1-x_{1}=n

\end{aligned}

$$

Equality is achieved when $x_{1}=x_{2}=\ldots=x_{n}=1 / 2$.

## Answer

$\frac{n}{\sqrt{2}}$.

| 4.33

|

10,11

There is a piece of chain consisting of 150 links, each weighing 1 g. What is the smallest number of links that need to be broken so that from the resulting parts, all weights of 1 g, 2 g, 3 g, ..., 150 g can be formed (a broken link also weighs 1 g)?

|

\text{4}

|

Answer: 4 links. According to the solution of problem 5 for grades $7-8$, for a chain consisting of $n$ links, where $64 \leq n \leq 159$, it is sufficient to unfasten 4 links.

| 4.2

|

$12.23 y=\frac{x}{\ln x}$.

The above text is translated into English, please retain the original text's line breaks and format, and output the translation result directly.

However, since the provided text is already in a mathematical format which is universal and does not require translation, the translation is as follows:

$12.23 y=\frac{x}{\ln x}$.

|

(e, e)

|

12.23 The function is defined for $x>0$ and $x \neq 1$. We have

$$

y^{\prime}=\frac{\ln x - x \cdot \frac{1}{x}}{\ln ^{2} x}=\frac{\ln x - 1}{\ln ^{2} x}

$$

Thus, $y^{\prime}=0$ when $\ln x - 1 = 0$, i.e., when $x=e$. Let's construct a table:

| Interval | $(0,1)$ | $(1, e)$ | $e$ | $(e, \infty)$ |

| :---: | :---: | :---: | :---: | :---: |

| $y^{\prime}$ | - | - | 0 | + |

| $y$ | $\searrow$ | $\searrow$ | $\min$ | $\nearrow$ |

Therefore, the function has a minimum at $x=e$. Let's find the value of the function at $x=e$:

$$

y_{\min }=y(e)=\frac{e}{\ln e}=e

$$

Answer: $(e ; e)$ is the point of minimum.

| 3.5

|

6. A factory produces sets of $n>2$ elephants of different sizes. According to the standard, the difference in mass between adjacent elephants within each set should be the same. The inspector checks the sets one by one using a balance scale without weights. For what smallest $n$ is this possible?

|

$n=5$

|

- Omвem: for $n=5$. Let's number the elephants in ascending order of their size, then it is enough to verify that $C_{1}+C_{4}=C_{2}+C_{3}, C_{1}+C_{5}=C_{2}+C_{4}$ and $C_{2}+$ $C_{5}=C_{3}+C_{4}$. These equalities are equivalent to $C_{4}-C_{3}=C_{2}-C_{1}$, $C_{2}-C_{1}=C_{5}-C_{4}$ and $C_{5}-C_{4}=C_{3}-C_{2}$, that is, all adjacent differences are equal. For $n=4$, it is impossible to check, because the weight sets $10,11,12,13$ and $10,11,13,14$ will give the same result for any weighings.

(A. Shapovalov)

## Third Round

| 5

|

7.214. $9^{x}+6^{x}=2^{2 x+1}$.

Translate the above text into English, keeping the original text's line breaks and format, and output the translation result directly.

7.214. $9^{x}+6^{x}=2^{2 x+1}$.

|

0

|

Solution.

Rewrite the equation as $3^{2 x}+2^{x} \cdot 3^{x}-2 \cdot 2^{2 x}=0$ and divide it by $2^{2 x} \neq 0$. Then $\left(\frac{3}{2}\right)^{2 x}+\left(\frac{3}{2}\right)^{x}-2=0 \Rightarrow\left(\left(\frac{3}{2}\right)^{x}\right)=-2$ (no solutions) or $\left(\left(\frac{3}{2}\right)^{x}\right)_{2}=1 \Rightarrow x=0$.

Answer: 0.

| 3

|

After a fair die with faces numbered 1 to 6 is rolled, the number on the top face is $x$. What is the most likely outcome?

|

x > 2

|

With a fair die that has faces numbered from 1 to 6, the probability of rolling each of 1 to 6 is $\frac{1}{6}$. We calculate the probability for each of the five choices. There are 4 values of $x$ that satisfy $x>2$, so the probability is $\frac{4}{6}=\frac{2}{3}$. There are 2 values of $x$ that satisfy $x=4$ or $x=5$, so the probability is $\frac{2}{6}=\frac{1}{3}$. There are 3 values of $x$ that are even, so the probability is $\frac{3}{6}=\frac{1}{2}$. There are 2 values of $x$ that satisfy $x<3$, so the probability is $\frac{2}{6}=\frac{1}{3}$. There is 1 value of $x$ that satisfies $x=3$, so the probability is $\frac{1}{6}$. Therefore, the most likely of the five choices is that $x$ is greater than 2.

| 1.2

|

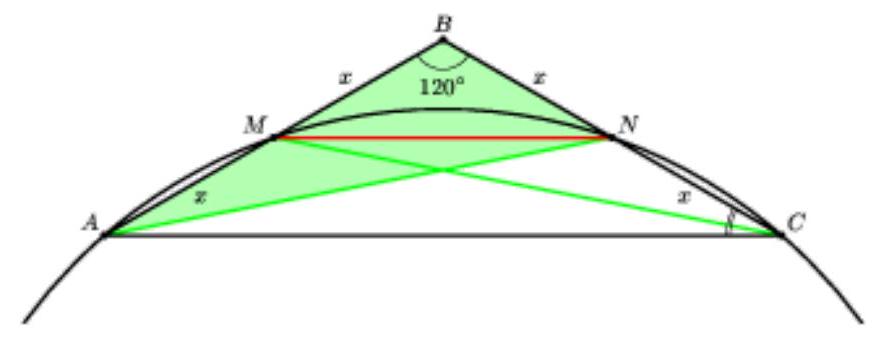

25 Two equilateral triangles overlap to form a six-pointed star (as shown in the figure). The first 12 positive integers 1, $2, \cdots, 12$ are to be placed at the 12 nodes of the figure, such that the sum of the four numbers on each straight line is equal.

(1) Find the minimum sum of the numbers placed at the six vertices $a_{1}$, $a_{2}, \cdots, a_{6}$ of the six-pointed star;

(2) Prove that the number of different filling schemes that satisfy the condition is even. (For filling schemes $\pi$ and $T$, if scheme $\pi$ can be rotated or flipped to coincide with scheme $T$, they are considered the same filling scheme)

|

24

|

(1) For any filling method that satisfies the conditions, the number filled at point $a_{i}$ is still denoted as $a_{i}, i=1,2, \cdots, 12$. If the sum of the four numbers on each line is $s$, then from $6 s=2(1+2+\cdots+12)$, we get $s=26$;

In $\triangle a_{1} a_{3} a_{5}$, on the three sides, we have

$$

\begin{array}{l}

\left(a_{1}+a_{8}+a_{9}+a_{3}\right)+\left(a_{3}+a_{10}+a_{11}+a_{5}\right) \\

\quad+\left(a_{5}+a_{12}+a_{7}+a_{1}\right)=3 s ;

\end{array}

$$

In $\triangle a z a_{4} a_{6}$, on the three sides, we have

$$

\begin{array}{l}

\left(a_{2}+a_{9}+a_{10}+a_{4}\right)+\left(a_{4}+a_{11}+a_{12}+a_{6}\right) \\

\quad+\left(a_{6}+a_{7}+a_{8}+a_{2}\right)=3 s .

\end{array}

$$

Subtracting the two equations, we get $a_{1}+a_{3}+a_{5}=a_{2}+a_{4}+a_{6}$.

From this, we know that the sum of the numbers at the vertices of the two triangles is equal. If we denote $m=\left(a_{1}+a_{3}+\right.$ $\left.a_{5}\right)+\left(a_{2}+a_{4}+a_{6}\right)$, then $m$ is an even number.

Because in $1,2, \cdots, 12$, the sum of the smallest six numbers $1+2+\cdots+6=21$ is odd, then $m \geqslant 22$. If $m=22$, since in $1,2, \cdots, 12$, the sum of six numbers that equals 22 is only $1,2,3,4,5,7$, dividing these into two groups with equal sums, there is only one unique division:

$$

\{1,3,7\} \text { and }\{2,4,5\} \text {. }

$$

Now, ignoring the specific numbers on the outer circle, and changing $\{1,3,7\}$ and $\{2,4,5\}$ to $\{$ odd, odd, odd $\}$ and $\{$ even, even, odd $\}$, respectively, then under rotation, the filling method of the six vertices is unique.

Now consider the filling method of the six inner numbers. Using the notation $a \sim b$ to indicate that integers $a, b$ have the same parity, since the sum of the four numbers on each line $s$ is even, then $a_{9} \sim a_{8} \sim a_{7} \sim a_{12}, a_{10} \sim$ $a_{11}$, and in the six inner numbers $6, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12$, there are exactly four even numbers and two odd numbers, so $\left\{a_{10}, a_{11}\right\}=\{9,11\}$. Since $a_{10}, a_{11}$ are on one side of the triangle with odd vertices, the sum of the numbers at the two vertices of that side should be $s-(9+11) = 6$, but in $\{1,3,7\}$, there are no two numbers that sum to 6, which is a contradiction. Therefore, $m \neq 22$, and thus the even number $m \geqslant 24$.

When $m=24$, we can actually provide a filling method that meets the requirements (as shown in the figure), so the minimum value sought is 24.

(2) For any filling method $\pi$ that satisfies the conditions, let the numbers at each point be $a_{1}, a_{2}, \cdots, a_{12}$, and let

$$

b_{i}=13-a_{i}, i=1,2, \cdots, 12,

$$

then when $a_{i} \in\{1,2, \cdots, 12\}$, $b_{i} \in\{1,2, \cdots, 12\}$. Now, in the filling method $\pi$, replace $a_{1}, a_{2}, \cdots, a_{12}$ with $b_{1}, b_{2}, \cdots, b_{12}$, to get the filling method $T$, then $T$ is also a filling method that satisfies the conditions; obviously

$$

\sum_{i=1}^{6} a_{i}+\sum_{i=1}^{6} b_{i}=\sum_{i=1}^{6}\left(a_{i}+b_{i}\right)=78,

$$

and $\sum_{i=1}^{6} a_{i}, \sum_{i=1}^{6} b_{i}$ are both even numbers, so $\sum_{i=1}^{6} a_{i} \neq 39, \sum_{i=1}^{6} b_{i} \neq 39$.

Let the set of all filling methods that satisfy the conditions be $M$, and divide $M$ into two disjoint subsets: $M=M_{1} \cup M_{2}$, where, in $M_{1}$, each filling method $\pi_{1}=\left(a_{1}, a_{2}, \cdots\right.$, $a_{12}$ ), the sum of the numbers at the six vertices $\sum_{i=1}^{6} a_{i}39$.

Make a correspondence between the filling method $\pi_{1}=\left(a_{1}, a_{2}, \cdots, a_{12}\right)$ in $M_{1}$ and the filling method $\pi_{2}=$ $\left(b_{1}, b_{2}, \cdots, b_{12}\right)$ in $M_{2}$, such that $b_{i}=13-a_{i}, i=1,2, \cdots, 12$, this correspondence is one-to-one, therefore, $\left|M_{1}\right|=\left|M_{2}\right|, M_{1} \cap M_{2}=\varnothing$, and $|M|=$ $\left|M_{1} \cup M_{2}\right|=2\left|M_{1}\right|$, i.e., the number of elements in $M$ is even. That is, the number of different filling methods that satisfy the conditions is even.

| 5.2

|

2. The coordinates $(x ; y)$ of points in the square $\{(x ; y):-\pi \leq x \leq \pi, 0 \leq y \leq 2 \pi\}$ satisfy the system of equations $\left\{\begin{array}{c}\sin x+\sin y=\sin 2 \\ \cos x+\cos y=\cos 2\end{array}\right.$. How many such points are there in the square? Find the coordinates $(x ; y)$ of the point with the smallest ordinate.

|

\left(2+\frac{\pi}{3}, 2-\frac{\pi}{3}\right)

|

Answer: 1) two points

$$

\text { 2) } x=2+\frac{\pi}{3}, y=2-\frac{\pi}{3}

$$

| 2.25

|

9. Let $a+b=1, b>0, a \neq 0$, then the minimum value of $\frac{1}{|a|}+\frac{2|a|}{b}$ is

Translate the above text into English, please retain the original text's line breaks and format, and output the translation result directly.

|

2 \sqrt{2}-1

|

Solve $2 \sqrt{2}-1$.

Analysis $\frac{1}{|a|}+\frac{2|a|}{b}=\frac{a+b}{|a|}+\frac{2|a|}{b}=\frac{a}{|a|}+\left(\frac{b}{|a|}+\frac{2|a|}{b}\right) \geq \frac{a}{|a|}+2 \sqrt{\frac{b}{|a|} \cdot \frac{2|a|}{b}}=2 \sqrt{2}+\frac{a}{|a|}$, where the equality holds when $\frac{b}{|a|}=\frac{2|a|}{b}$, i.e., $b^{2}=2 a^{2}$.

When $a>0$, $\frac{1}{|a|}+\frac{2|a|}{b} \geq 2 \sqrt{2}+1$, the minimum value is reached when $a=\sqrt{2}-1, b=\sqrt{2} a=2-\sqrt{2}$; when $a<0$, $\frac{1}{|a|}+\frac{2|a|}{b} \geq 2 \sqrt{2}-1$, the minimum value $2 \sqrt{2}-1$ is reached when $a=-(\sqrt{2}+1), b=-\sqrt{2} a$.

| 9

|

25. A scout is in a house with four windows arranged in a rectangular shape. He needs to signal to the sea at night by lighting a window or several windows. How many different signals can he send?

|

10

|

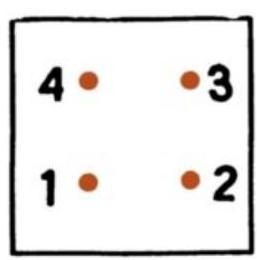

25. Let's schematically represent the windows and measure them:

a) Lighting all four windows gives one signal;

b) Lighting one of the windows is perceived as one signal, as in the dark, the position of the windows relative to the house cannot be distinguished;

c) Lighting two windows can give 4 different signals: one signal by lighting windows 1,4 or 2,3; one signal by lighting windows 1,2 or 4,3; two signals by lighting windows 1,3 and 2,4, i.e., we have the following configurations:

1)

2) $\bullet \cdot 3)$

- 4)

d) Lighting three windows can give four signals: $1,2,3$; $2,3,4$; $3,4,1$ and $4,1,2$, i.e., we have the following configurations:

1)

2)

3)

4)

In total, we have different signals: $1+1+4+4=10$.

| 1.6

|

6.014. $\frac{4}{x^{2}+4}+\frac{5}{x^{2}+5}=2$.

|

$x=0$

|

## Solution.

Domain: $x \in R$.

$\frac{2 x^{4}+9 x^{2}}{\left(x^{2}+4\right)\left(x^{2}+5\right)}=0 \Leftrightarrow 2 x^{4}+9 x^{2}=0 \Leftrightarrow x^{2}\left(2 x^{2}+9\right)=0$,

$x^{2}=0, x_{1}=0$ or $2 x^{2}+9=0, x_{2,3} \in \varnothing$.

Answer: $x=0$.

| 2

|

6. Find the greatest possible value of $\gcd(x+2015 y, y+2015 x)$, given that $x$ and $y$ are coprime numbers.

|

4060224

|

Answer: $2015^{2}-1=4060224$. Solution. Note that the common divisor will also divide $(x+2015 y)-2015(y+2015 x)=\left(1-2015^{2}\right) x$. Similarly, it divides $\left(1-2015^{2}\right) y$, and since $(x, y)=1$, it divides $\left(1-2015^{2}\right)$. On the other hand, if we take $x=1, y=2015^{2}-2016$, then we get $\gcd(x+2015 y, y+2015 x)=2015^{2}-1$.

| 8

|

3. Given $n^{2}$ points arranged in the plane in the form of a square grid $n \times n$. A broken line of length $l$ is the union of closed segments $A_{0} A_{1}$, $A_{1} A_{2}$, $A_{2} A_{3}, \ldots, A_{l-1} A_{l}$ in that plane. Determine the smallest natural number $l$ for which there exists a broken line of length $l$ on which all $n^{2}$ observed points lie.

|

$2n-2$

|

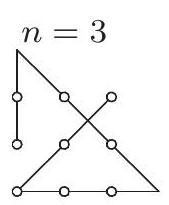

3. Let the desired value of the number $l$ be denoted by $l_{n}$. Trivially, $l_{1}=1$ and $l_{2}=3$. The examples in the figure show that $l_{3} \leqslant 4$ and, in general, $l_{n} \leqslant 2 n-2$ for $n \geqslant 3$.

Assume that the broken line $\mathcal{C}$ of length $l$ covers all $n^{2}$ points. Let there be $a$ horizontal and $b$ vertical segments among the segments of the line $\mathcal{C}$. The remaining $l-a-b$ segments of the line $\mathcal{C}$

are bent by horizontal and vertical

segments to form a rectangular grid $S$ of dimensions $(n-a) \times(n-b)$.

- If $a \geqslant n$ (analogously for $b \geqslant n$), there is no grid $S$, but at least $n-1$ segments are needed to connect $n$ horizontal segments, so $l \geqslant 2 n-1$.

- If $a=n-1$ (analogously for $b=n-1$), the grid $S$ consists of $n-b$ points, and each diagonal segment covers at most one, so we need at least $n-b$ more segments, which gives a total of $l \geqslant(n-1)+b+(n-b)=2 n-1$ segments.

- If $a<n-2$ and $b<n-2$, the convex hull of the grid $S$ consists of $2(2 n-a-b-2)$ points, and each diagonal segment covers at most two, so we need at least $2 n-a-b-2$ more segments. Thus, in total, we have $l \geqslant a+b+(2 n-a-b-2)=2 n-2$ segments.

Therefore, $l_{n}=2 n-2$ for all $n \geqslant 3$.

| 3.4

|

2. Find all positive integers $n$ $(n \geqslant 3)$ such that there exists a set $M$ with $n$ elements, where the elements are distinct non-zero vectors of equal length, and the following conditions are satisfied: $\sum_{u \in M} u=0$, and for any $v, w \in M$, $\boldsymbol{v}+\boldsymbol{w} \neq \mathbf{0}$.

|

\{n \in \mathbf{N} \mid n \geqslant 3, n \neq 4\}

|

2. First, for any odd number $n$ not less than 3, take $M$ as the $n$ distinct complex roots of the equation $z^{n}-1=0$. Clearly, the set $M$ satisfies the requirements.

Next, consider even numbers $n$ not less than 6.

Let $\frac{n}{2}=k$, first consider the decomposition of $\frac{1}{2}$.

From $\frac{1}{n}=\frac{1}{n+1}+\frac{1}{n(n+1)}$, we know that $\frac{1}{2}$ can be decomposed into the sum of $k-1$ distinct unit fractions.

Assume $\frac{1}{2}=a_{1}+a_{2}+\cdots+a_{k-1}$, first take $k$ unit vectors above the $x$-axis, whose x-coordinates are sequentially $\frac{1}{2},-a_{1}, \cdots,-a_{n}$, then reflect these vectors about the $x$-axis to get $n$ vectors. Let this set of $n$ vectors be $M$, clearly the set $M$ satisfies the conditions.

Finally, prove that $n=4$ does not satisfy the conditions.

Assume the four vectors are $(1,0),\left(x_{1}, y_{1}\right)$, $\left(x_{2}, y_{2}\right),\left(x_{3}, y_{3}\right)$. To satisfy the conditions, we need $y_{i} \neq 0$ $(i=1,2,3)$.

Assume $y_{1}>0, y_{2}>0, y_{3}<0$. At this point,

$$

\begin{array}{l}

x_{1}+x_{2}+x_{3}=-1, \\

y_{1}+y_{2}+y_{3}=0, \\

x_{i}^{2}+y_{i}^{2}=1(i=1,2,3) . \\

\text { Then }\left\{\begin{array}{l}

\sqrt{1-x_{1}^{2}}+\sqrt{1-x_{2}^{2}}=-y_{3}, \\

x_{1}+x_{2}=-1-x_{3} .

\end{array}\right. \\

(1)^{2}+(2)^{2} \text { gives } \\

x_{1} x_{2}+\sqrt{1-x_{1}^{2}-x_{2}^{2}+x_{1}^{2} x_{2}^{2}}=x_{3} . \\

\text { Let }\left\{\begin{array}{l}

x_{1}+x_{2}=a, \\

x_{1} x_{2}=b .

\end{array}\right.

\end{array}

$$

Substituting into equation (3) gives

$$

\begin{array}{l}

b+\sqrt{1-a^{2}+2 b+b^{2}}=-a-1 \\

\Rightarrow a(a+b+1)=0 .

\end{array}

$$

If $a=0$, then $x_{3}=-1$, at this time, $y_{3}=0$, which is a contradiction.

If $a+b+1=0$, it can be deduced that

$$

\left(x_{1}+1\right)\left(x_{2}+1\right)=0 \text {, }

$$

At this time, $y_{1}$ or $y_{2}$ must be 0, which is a contradiction.

In summary, the solution is $\{n \in \mathbf{N} \mid n \geqslant 3, n \neq 4\}$.

| 3

|

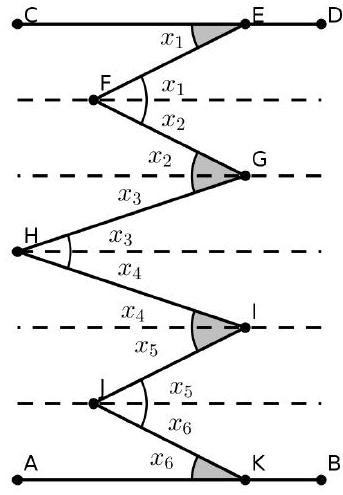

Isosceles $\triangle ABC$ has equal side lengths $AB$ and $BC$. In the figure below, segments are drawn parallel to $\overline{AC}$ so that the shaded portions of $\triangle ABC$ have the same area. The heights of the two unshaded portions are 11 and 5 units, respectively. What is the height of $h$ of $\triangle ABC$?

$\textbf{(A) } 14.6 \qquad \textbf{(B) } 14.8 \qquad \textbf{(C) } 15 \qquad \textbf{(D) } 15.2 \qquad \textbf{(E) } 15.4$

|

14.6

|

First, we notice that the smaller isosceles triangles are similar to the larger isosceles triangles. We can find that the area of the gray area in the first triangle is $[ABC]\cdot\left(1-\left(\tfrac{11}{h}\right)^2\right)$. Similarly, we can find that the area of the gray part in the second triangle is $[ABC]\cdot\left(\tfrac{h-5}{h}\right)^2$. These areas are equal, so $1-\left(\frac{11}{h}\right)^2=\left(\frac{h-5}{h}\right)^2$. Simplifying yields $10h=146$ so $h=\boxed{\textbf{(A) }14.6}$.

~MathFun1000 (~edits apex304)

| 2.75

|

12. Given that $m, n, t (m<n)$ are all positive integers, points $A(-m, 0), B(n, 0), C(0, t)$, and $O$ is the origin. Suppose $\angle A C B=90^{\circ}$, and

$$

O A^{2}+O B^{2}+O C^{2}=13(O A+O B-O C) \text {. }

$$

(1) Find the value of $m+n+t$;

(2) If the graph of a quadratic function passes through points $A, B, C$, find the expression of this quadratic function.

|

$y = -\frac{1}{3} x^{2} + \frac{8}{3} x + 3$

|

12. (1) According to the problem, we have

$$

O A=m, O B=n, O C=t \text {. }

$$

From $\angle A C B=90^{\circ}, O C \perp A B$, we get

$$

O A \cdot O B=O C^{2} \Rightarrow m n=t^{2} \text {. }

$$

From the given equation, we have

$$

\begin{array}{l}

m^{2}+n^{2}+t^{2}=13(m+n-t) . \\

\text { Also, } m^{2}+n^{2}+t^{2} \\

=(m+n+t)^{2}-2(m n+n t+t m) \\

=(m+n+t)(m+n-t),

\end{array}

$$

$$

\text { Therefore, }(m+n+t)(m+n-t)=13(m+n-t) \text {. }

$$

From the given, $m+n-t \neq 0$, thus,

$$

m+n+t=13 \text {. }

$$

(2) From $m n=t^{2}, m+n=13-t(m0 \\

\Rightarrow(3 t-13)(t+13)<0 \\

\Rightarrow-13<t<\frac{13}{3} .

\end{array}

$$

Since $t$ is a positive integer, we have $t=1,2,3,4$.

When $t=1,2,4$, we get the equations respectively

$$

\begin{array}{l}

x^{2}-12 x+1=0, \\

x^{2}-11 x+4=0, \\

x^{2}-9 x+16=0,

\end{array}

$$

None of the above equations have integer solutions;

When $t=3$, we get the equation

$$

x_{1}^{2}-10 x+9=0 \text {, }

$$

Solving it, we get $m=1, n=9$.

Thus, $t=3, m=1, n=9$.

Therefore, the points are $A(-1,0), B(9,0), C(0,3)$.

Assume the quadratic function is

$$

y=a(x+1)(x-9) \text {. }

$$

Substituting the coordinates of point $C(0,3)$ into the above equation, we get

$$

a=-\frac{1}{3} \text {. }

$$

Hence, $y=-\frac{1}{3}(x+1)(x-9)$

$$

\Rightarrow y=-\frac{1}{3} x^{2}+\frac{8}{3} x+3 \text {. }

$$

| 3

|

497. Shuffling Cards. An elementary method of shuffling cards consists of taking a deck face down in the left hand and transferring the cards one by one to the right hand; each successive card is placed on top of the previous one: the second on top of the first, the fourth on top of the third, and so on until all the cards have been transferred. If you repeat this procedure several times with any even number of cards, you will find that after a certain number of repeated shuffles, the cards will return to their original order. If you have \(2,4,8,16,32,64\) cards, it will take \(2,3,4,5\), 6,7 shuffles respectively for the cards to return to their original order.

\footnotetext{

* The correct order is: Ace, Two, Three, Four, Five, Six, Seven, Eight, Nine, Ten, Jack, Queen, King.

}

How many times do you need to shuffle a deck of 14 cards?

|

14

|

497. To shuffle 14 cards in the manner described above and return them to their original order, it takes 14 shuffles, although in the case of 16 cards, only 5 are required. We cannot delve into the nature of this phenomenon here, but the reader may find it interesting to conduct an independent investigation of this question.

[For the mathematical theory of such shuffling, see W. W. Rouse Ball, “Mathematical Recreations and Essays” (N. Y., 1960, pp. 310-311). This shuffling is sometimes called “Monge’s shuffle,” after the famous 18th-century French mathematician Gaspard Monge, who first invented it. M. G.]

| 4

|

5. The number of real roots of the equation $\frac{\left(x^{2}-x+1\right)^{3}}{x^{2}(x-1)^{2}}=\frac{\left(\pi^{2}-\pi+1\right)^{3}}{\pi^{2}(\pi-1)^{2}}$ with respect to $x$ is exactly $($ )

A. 1

B. 2

C. 4

D. 6

|

6

|

5. D

From the given conditions, it is clear that $x=\pi$ is a root of the original equation. Let's denote the left side as $f(x)$. It is easy to verify:

$$

f\left(\frac{1}{x}\right)=f(x), f(1-x)=f(x), f\left(\frac{1}{1-x}\right)=f(x), f\left(1-\frac{1}{x}\right)=f

$$

$(x), f\left(\frac{x}{x-1}\right)=f(x)$. Therefore, the original equation has exactly 6 distinct real roots: $\pi, \frac{1}{\pi}, 1-\pi$,

$$

\frac{1}{1-\pi}, 1-\frac{1}{\pi}, \frac{\pi}{\pi-1} .

$$

| 5

|

7. From the sides and diagonals of a regular 12-sided polygon, three different segments are randomly selected. The probability that their lengths are the side lengths of a triangle is $\qquad$

|

\frac{223}{286}

|

7. $\frac{223}{286}$.

Let the diameter of the circumscribed circle of a regular 12-sided polygon be 1. Then, the lengths of all $\mathrm{C}_{12}^{2}=66$ line segments fall into 6 categories, which are

$$

\begin{array}{l}

d_{1}=\sin 15^{\circ}=\frac{\sqrt{6}-\sqrt{2}}{4}, \\

d_{2}=\sin 30^{\circ}=\frac{1}{2}, \\

d_{3}=\sin 45^{\circ}=\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2} \text { (please note) } \\

d_{4}=\sin 60^{\circ}=\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}, \\

d_{5}=\sin 75^{\circ}=\frac{\sqrt{6}+\sqrt{2}}{4}, \\

d_{6}=1,

\end{array}

$$

Among them, $d_{1}, d_{2}, \cdots, d_{5}$ each have 12 segments, and $d_{6}$ has 6 segments.

Clearly, the combinations that cannot form a triangle are of the following four types:

$(2,2,6)$ type, with $\mathrm{C}_{12}^{2} \mathrm{C}_{6}^{1}$ ways;

$(1,1, k)(k \geqslant 3)$ type, with $\mathrm{C}_{12}^{2} \mathrm{C}_{42}^{1}$ ways;

$(1,2, k)(k \geqslant 4)$ type, with $\mathrm{C}_{12}^{1} \mathrm{C}_{12}^{1} \mathrm{C}_{30}^{2}$ ways;

$(1,3, k)(k \geqslant 5)$ type, with $\mathrm{C}_{12}^{1} \mathrm{C}_{12}^{1} \mathrm{C}_{30}^{2}$ ways.

Therefore, the required probability is $1-\frac{63}{286}=\frac{223}{286}$.

| 7

|

Riley has 64 cubes with dimensions $1 \times 1 \times 1$. Each cube has its six faces labelled with a 2 on two opposite faces and a 1 on each of its other four faces. The 64 cubes are arranged to build a $4 \times 4 \times 4$ cube. Riley determines the total of the numbers on the outside of the $4 \times 4 \times 4$ cube. How many different possibilities are there for this total?

|

49

|

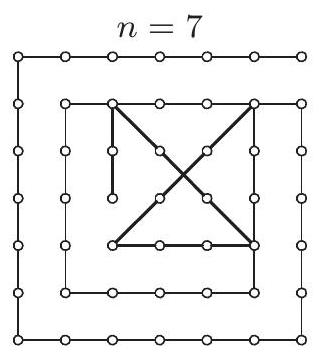

We can categorize the 64 small cubes into four groups: 8 cubes that are completely in the interior of the larger cube (and are completely invisible), $4 \times 6=24$ "face cubes" that have exactly one of their faces showing, $2 \times 12=24$ "edge cubes" that have exactly two faces showing, and 8 "corner cubes" that have 3 faces showing.

Notice that $8+24+24+8=64$, so this indeed accounts for all 64 small cubes.

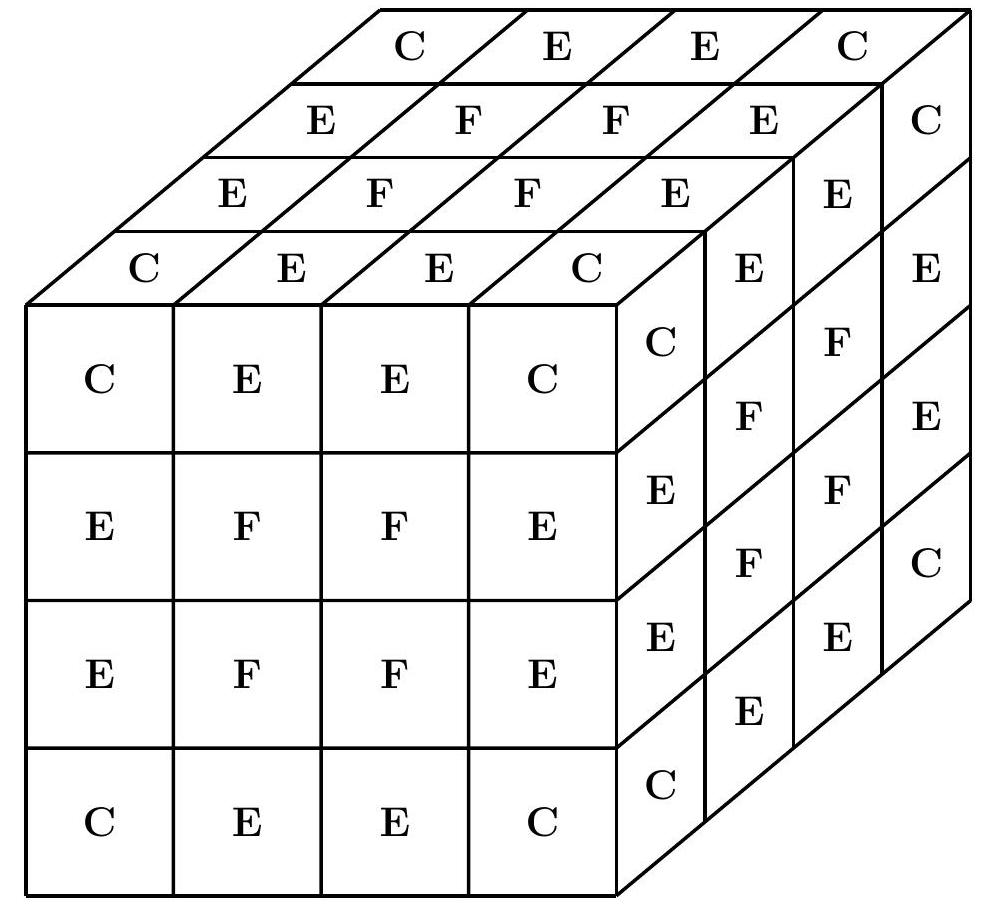

The diagram below has all visible faces of the smaller cubes labelled so that faces of edge cubes are labelled with an $\mathbf{E}$, faces of face cubes are labelled with an $\mathbf{F}$, and faces of corner cubes are labelled with a $\mathbf{C}$ :

Each of the 8 corner cubes has 3 of its faces exposed.

Because of the way the faces are labelled on the small cubes, each of the 8 corner cubes will always contribute a total of $1+1+2=4$ to the sum of the numbers on the outside.

Regardless of how the small cubes are arranged, the corner cubes contribute a total of $8 \times 4=32$ to the total of all numbers on the outside of the larger cube.

The edge cubes can each show either a 1 and a 1 or a 1 and a 2 , for a total of either 2 or 3 .

Thus, each edge cube contributes a total of either 2 or 3 to the total on the outside of the larger cube.

This means the smallest possible total that the edge cubes contribute is $24 \times 2=48$, and the largest possible total that they contribute is $24 \times 3=72$.

Notice that it is possible to arrange the edge cubes to show any total from 48 to 72 inclusive.

This is because if we want the total to be $48+k$ where $k$ is any integer from 0 to 24 inclusive, we simply need to arrange exactly $k$ of the edge cubes to show a total of 3 .

Each of the face cubes shows a total of 1 or a total of 2 . There are 24 of them, so the total showing on the face cubes is at least 24 and at most $24 \times 2=48$.

Similar to the reasoning for the edge cubes, every integer from 24 to 48 inclusive is a possibility for the total showing on the face cubes.

Therefore, the smallest possible total is $32+48+24=104$, and the largest possible total is $32+72+48=152$.

By earlier reasoning, every integer between 104 and 152 inclusive is a possibility, so the number of possibilities is $152-103=49$.

ANSWER: 49

| 4

|

16. Given the six-digit number $\overline{9786 \square}$ is a multiple of $\mathbf{99}$, the quotient when this six-digit number is divided by $\mathbf{99}$ is ( ).

|

6039

|

$\begin{array}{l}\text { [Analysis] Let } 99 \mid \overline{A 9786 B} \text {, sum of pairs from right to left } \\ 99 \mid \overline{A 9}+78+\overline{6 B} \text {, i.e., } 99|78+69+\overline{A B} \Rightarrow 99| 48+\overline{A B} \\ \overline{A B}=51 \text {, i.e., } \mathrm{A}=5, \mathrm{~B}=1 \\ 597861 \div 99=6039\end{array}$

| 1.5

|

The base of the right prism $A B C A_{1} B_{1} C_{1}$ is an isosceles triangle $A B C$, where $A B=B C=5$, $\angle A B C=2 \arcsin 3 / 5$. A plane perpendicular to the line $A_{1} C$ intersects the edges $A C$ and $A_{1} C_{1}$ at points $D$ and $E$ respectively, such that $A D=1 / 3 A C, E C_{1}=1 / 3 A_{1} C_{1}$. Find the area of the section of the prism by this plane.

|

\frac{40}{3}

|

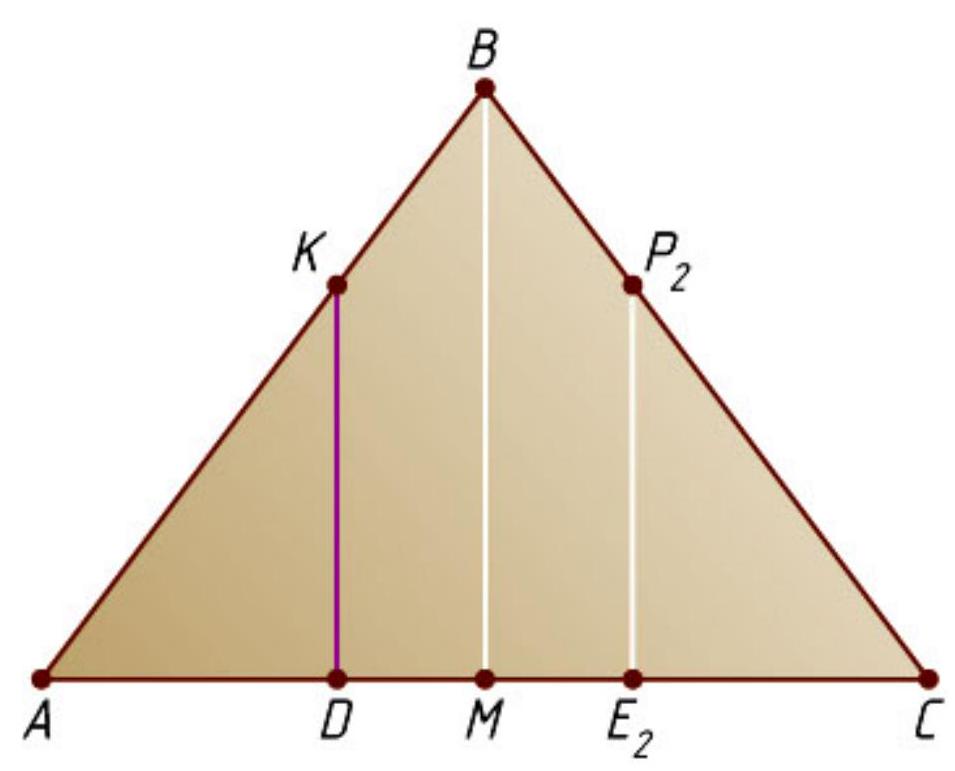

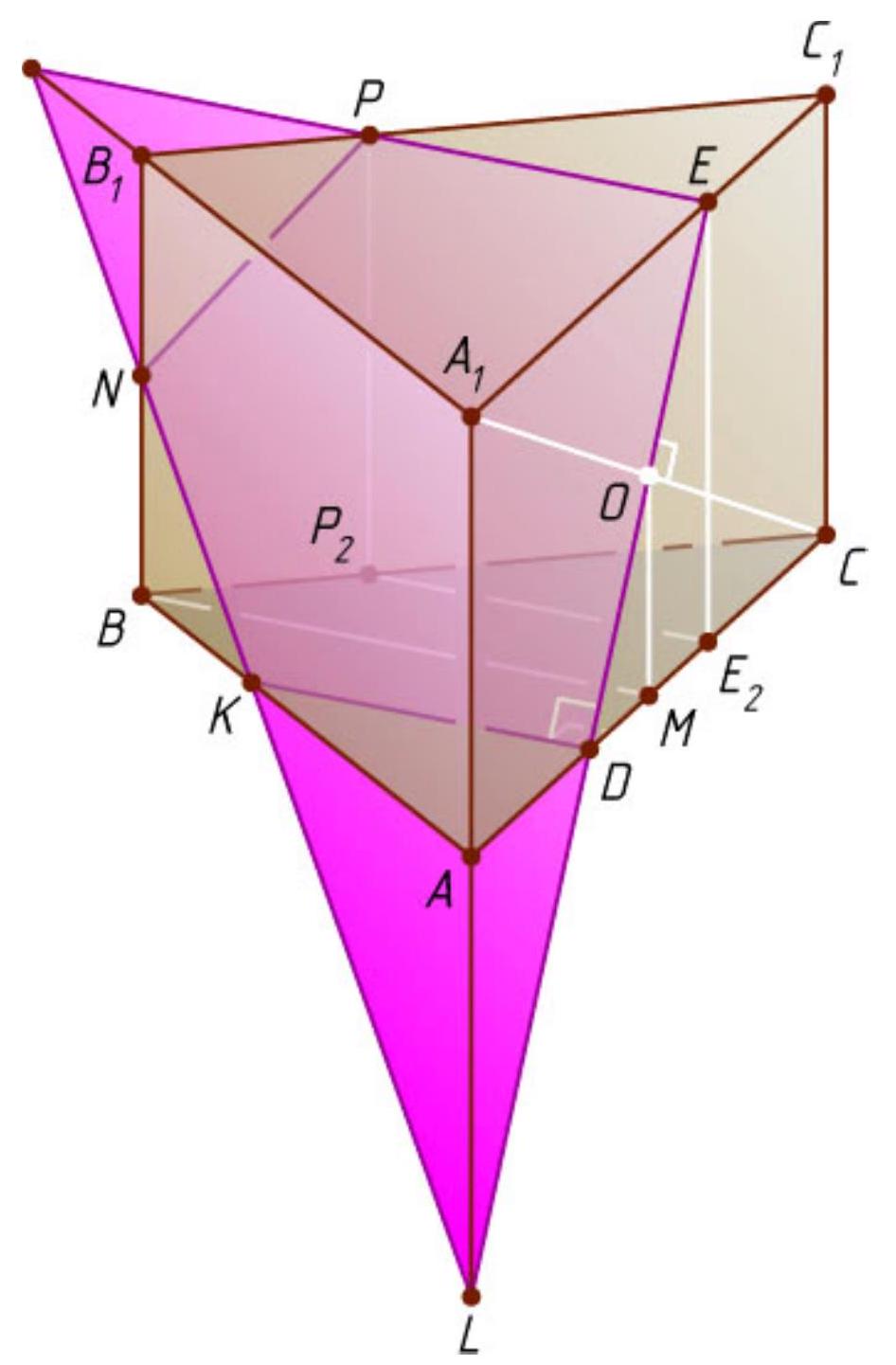

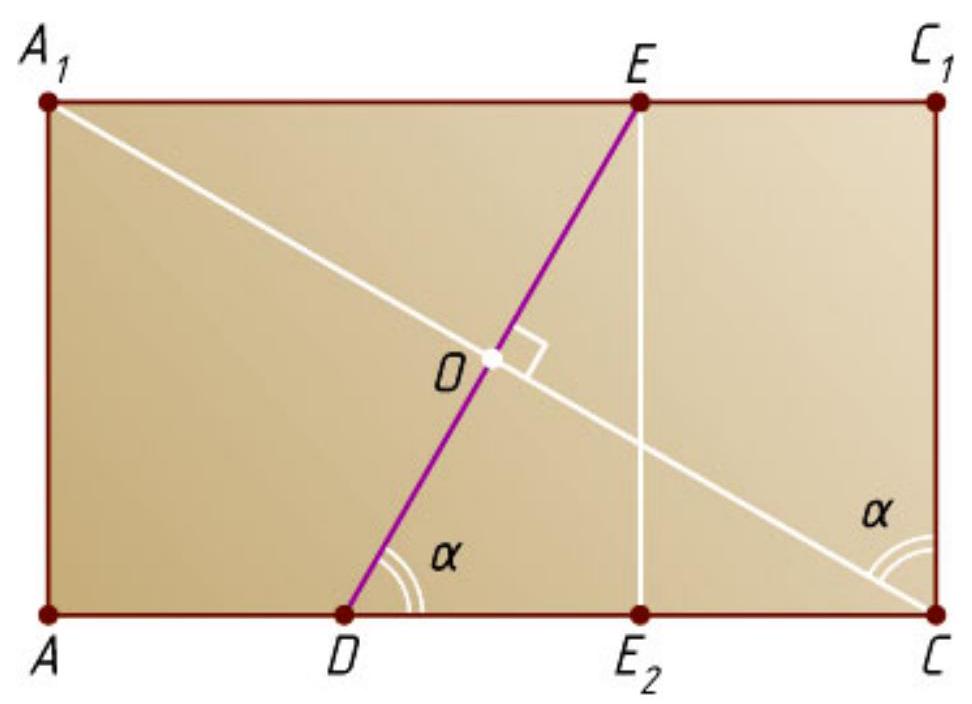

Let $M$ be the midpoint of the base $AC$ of the isosceles triangle $ABC$ (Fig. 1). From the right triangle $AMB$ we find that

Fig. 1

Fig. 2

Fig. 3

$AM = AB \sin \angle ABM = 5 \cdot \begin{aligned} & 3 \\ & 5\end{aligned} = 3, \quad BM = \sqrt{AB^2 - AM^2} = \sqrt{25 - 9} = 4$.

Then

$AC = 2AM = 6, \quad AD = \frac{1}{3}AC = 2, \quad C_1E = \frac{1}{3}A_1C_1 = 2$.

Since the line $A_1C$ is perpendicular to the cutting plane (Fig. 2), then $A_1C \perp DE$. Let $O$ be the intersection point of segments $A_1C$ and $DE$. From the equality of right triangles $A_1OE$ and $COD$ (by hypotenuse and acute angle), it follows that $O$ is the midpoint of $A_1C$. Therefore, the perpendicular dropped from point $O$ to $AC$ passes through point $M$, and since the prism is straight, this perpendicular lies in the plane of the face $AA_1C_1C$.

Let $K$ be the intersection point of the cutting plane with the line $AB$. The line $A_1C$ is perpendicular to the cutting plane containing the line $DK$, so $A_1C \perp DK$. By the theorem of three perpendiculars, $DK \perp AC$, since $AC$ is the orthogonal projection of the inclined line $A_1C$ onto the plane $ABC$. Triangles

$ADK$ and $AMB$ are similar with a coefficient $k = \frac{AD}{AM} = \frac{2}{3}$, so

$AK = k \cdot AB = \frac{2}{3} AB < AB$.

Thus, point $K$ lies on the segment $AB$. Similarly, point $P$ of the intersection of the plane with the line $B_1C_1$ lies on the edge $B_1C_1$. In this case, $EP \parallel DK$ and $EP = DK$.

Let the lines $ED$ and $AA_1$ intersect at point $L$, and the lines $LK$ and $BB_1$ intersect at point $N$. Then the section of the prism in question is the pentagon $DKNPE$. Its orthogonal projection onto the plane $ABC$ is the pentagon $DKBP_2E_2$ (Fig. 1, 2), where $P_2$ and $E_2$ are the orthogonal projections of points $P$ and $E$ onto the plane $ABC$. Then

$S_{\triangle CE_2P_2} = S_{\triangle ADK} = k^2 \cdot S_{\triangle AMB} = k^2 \cdot \frac{1}{2} \cdot AM \cdot BM = \left(\frac{2}{3}\right)^2 \cdot \frac{1}{2} \cdot 3 \cdot 4 = \frac{8}{3}$,

$S_{DKBP_2E_2} = S_{\triangle ABC} - 2S_{\triangle ADK} = \frac{1}{2} \cdot AC \cdot BM - 2S_{\triangle ADK} = \frac{1}{2} \cdot 6 \cdot 4 - 2 \cdot \frac{8}{3} = \frac{20}{3}$.

Let $h$ be the height (lateral edge) of the prism. Consider the face $AA_1C_1C$ (Fig. 3). Denote $\angle A_1CC_1 = \angle EE_2D = \alpha$. From the right triangles $CA_1C_1$ and $DEE_2$ we find that

$\tan \alpha = \frac{A_1C_1}{CC_1} = \frac{6}{h}$ and $\tan \alpha = \frac{EE_2}{DE_2} = \frac{h}{2}$,

from which $h = 2\sqrt{3}$ and $\tan \alpha = \sqrt{3}$. Therefore, $\alpha = 60^\circ$.

Since $CD \perp KD$ and $ED \perp KD$, the angle $EDC$ is the linear angle of the dihedral angle between the cutting plane and the plane $ABC$, and since $\angle EDC = \alpha = 60^\circ$, then, by the theorem of the area of the orthogonal projection of a polygon,

$S_{DKNPE} = \frac{S_{DKBP_2E_2}}{\cos \alpha} = \frac{\frac{20}{3}}{\frac{1}{2}} = \frac{40}{3}$.

| 4.2

|

10. Real numbers $x, y$ satisfy $x^{2}+y^{2}=20$, then the maximum value of $x y+8 x+y$ is

Translate the above text into English, please retain the original text's line breaks and format, and output the translation result directly.

|

42

|

Rong Ge 42.

Analysis Note $x y \leq \frac{1}{4} x^{2}+y^{2}, 8 x \leq x^{2}+16, y \leq \frac{1}{4} y^{2}+1$, adding these three inequalities yields

$$

x y+8 x+y \leq \frac{5}{4}\left(x^{2}+y^{2}\right)+17=42

$$

and when $x=4, y=2$, the equality can be achieved, so the maximum value of $x y+8 x+y$ is 42.

Alternatively, the Cauchy inequality can be used directly

$$

(x y+8 x+y)^{2} \leq\left(x^{2}+8^{2}+y^{2}\right)\left(y^{2}+x^{2}+1^{2}\right)=84 \cdot 21=42^{2}

$$

yielding the maximum value of 42.

| 5

|

a) We have 3 initially empty urns. One of them is chosen at random with equal probability (1/3 for each). Then, a ball is placed inside the chosen urn. The process is repeated until one of the urns has two balls. What is the probability that when the process ends, the total number of balls in all urns is equal to 2?

b) Now we have 2014 initially empty urns. Repeating the same process as before, what is the probability that at the end there will be exactly 10 balls in the urns?

|

\frac{2013}{2014} \cdot \frac{2012}{2014} \cdot \frac{2011}{2014} \cdot \frac{2010}{2014} \cdot \frac{2009}{2014} \cdot \frac{2008}{2014} \cdot \frac{2007}{2014} \cdot \frac{2006}{2014} \cdot \frac{9}{2014}

|

Solution

a) First, a ball is placed in some urn. For the process to end with two balls, it is necessary that, in the next step, the next ball is placed in the same urn where the first ball was placed. This has a probability of 1/3. Therefore, the probability that the process ends with two balls is equal to $1 / 3$.

b) First, a ball is placed in some urn. In the next step, it is necessary that the next ball be placed in a different urn from the first one chosen. Otherwise, the process ends! Since there are 2013 empty urns (one is already occupied), the probability of this happening is

$$

\frac{2013}{2014}

$$

In the third step, a new urn is chosen. For the process not to end, it is necessary that this new urn chosen is different from the previous two. The probability of this happening is

$$

\frac{2012}{2014}

$$

In the fourth step, a new urn is chosen. By the same argument as before, the probability that the chosen urn is different from the previous ones is

$$

\frac{2011}{2014}

$$

and so on until the ninth urn, whose probability will be

$$

\frac{2006}{2014}

$$

For the process to end with ten balls, it is necessary that the tenth ball be placed in an urn that already has a ball! Since we have, up to this point, nine occupied urns and there are 2014 urns, the probability of this occurring is

$$

\frac{9}{2014}

$$

Thus, the probability that the process ends with 10 balls is equal to the product of the probabilities described above, which gives us

$$

\frac{2013}{2014} \cdot \frac{2012}{2014} \cdot \frac{2011}{2014} \cdot \frac{2010}{2014} \cdot \frac{2009}{2014} \cdot \frac{2008}{2014} \cdot \frac{2007}{2014} \cdot \frac{2006}{2014} \cdot \frac{9}{2014}

$$

as the result.

| 5.67

|

4. In acute triangle $A B C, M$ and $N$ are the midpoints of sides $A B$ and $B C$, respectively. The tangents to the circumcircle of triangle $B M N$ at $M$ and $N$ meet at $P$. Suppose that $A P$ is parallel to $B C$, $A P=9$ and $P N=15$. Find $A C$.

|

20 \sqrt{2}

|

Answer: $20 \sqrt{2}$

Solution: Extend rays $P M$ and $C B$ to meet at $Q$. Since $A P \| Q C$ and $M$ is the midpoint of $A B$, triangles $A M P$ and $B M Q$ are congruent. This gives $Q M=M P=P N=15$ and $Q B=A P=9$. Observe that the circumcircle of triangle $B M N$ is tangent to $Q M$, so by power of a point, we compute $Q M^{2}=Q B \cdot Q N$, which yields $Q N=25$. Applying Stewart's theorem on triangle $Q N P$, we have

$$

15 \cdot 15^{2}+15 \cdot 25^{2}=30 \cdot 15 \cdot 15+30 M N^{2} \text {, }

$$

which implies that $M N^{2}=\frac{1}{2}\left(25^{2}-15^{2}\right)=200$. Hence, as $M N$ is the midline of triangle $A B C$, we obtain $A C^{2}=4 M N^{2}=800$ and $A C=20 \sqrt{2}$.

| 6

|

6. In trapezoid $\mathrm{PQRS}$, it is known that $\angle \mathrm{PQR}=90^{\circ}, \angle Q R S>90^{\circ}$, diagonal $S Q$ is 24 and is the bisector of angle $S$, and the distance from vertex $R$ to line $Q S$ is 5. Find the area of trapezoid PQRS.

|

\frac{27420}{169}

|

Answer: $\frac{27420}{169}$.

Solution $\angle \mathrm{RQS}=\angle \mathrm{PSQ}$ as alternate interior angles, so triangle $\mathrm{RQS}$ is isosceles. Its height $\mathrm{RH}$ is also the median and equals 5. Then $S R=\sqrt{R H^{2}+S H^{2}}=13$. Triangles SRH and SQP are similar by two angles, the similarity coefficient is $\frac{S R}{S Q}=\frac{13}{24}$. Therefore, $P Q=\frac{24}{13} R H=\frac{120}{13}$, $P S=\frac{24}{13} S H=\frac{288}{13} \cdot$ The area of the trapezoid is $P Q \cdot \frac{Q R+P S}{2}=\frac{27420}{169}$.

| 6

|

97. There are 5 parts that are indistinguishable in appearance, 4 of which are standard and of the same mass, and one is defective, differing in mass from the others. What is the minimum number of weighings on a balance scale without weights that are needed to find the defective part?

|

3

|

$\triangle$ Let's number the parts. Now try to figure out the weighing scheme presented below (Fig. 32).

As can be seen from this, it took three weighings to find the defective part.

Answer: in three.

| 3

|

12. (6 points) There are 1997 odd numbers, the sum of which equals their product. Among them, three numbers are not 1, but three different prime numbers. Then, these three prime numbers are $\qquad$、$\qquad$、$\qquad$.

|

5, 7, 59

|

【Solution】Solution: According to the problem, we have: $1994+a+b+c=a b c$; when $a=3, b=5$, $15 c=c+2002, c=143$, which is not a prime number; when $a=3, b=7$, $21 c=c+2004, c=50 \frac{1}{5}$, which is not an integer; when $a=5, b=7$, $35 c=c+2006, c=59$, which satisfies the condition; therefore, the answer is: $5, 7, 59$.

| 5.5

|

10. Color the 6 regions $A, B, C, D, E, F$ in Figure 1, with each region being colored with 1 color, and no two adjacent regions having the same color. If there are 4 colors available, then there are $\qquad$ different coloring schemes.

|

96

|

10. 96

$A, B, C$ have different colors from each other. They have $4 \times$ $3 \times 2=24$ ways of coloring.

For any one of these (let's assume $A-a \quad B-b \quad C-c$. The other color is $d$), then $D$ can be colored with $b, d$, $E$ can be colored with $c, d$, and $F$ can be colored with $a, d$.

Since $D, E, F$ are adjacent to each other, at most 1 can be colored with $d$, so there are $1+3=4$ ways of coloring, thus the total number of different coloring methods is $4 \times 24=96$.

| 2.67

|

Given positive integers $a$, $b$, and $c$ satisfy $a^{2}+b^{2}-c^{2}=2018$.

Find the minimum values of $a+b-c$ and $a+b+c$.

|

2 \text{ and } 52

|

From the problem, we know

$$

a^{2}+b^{2}=c^{2}+2018 \equiv 2 \text { or } 3(\bmod 4)

$$

$\Rightarrow a, b$ are odd, $c$ is even

$$

\begin{array}{l}

\Rightarrow c^{2}+2018=a^{2}+b^{2} \equiv 2(\bmod 8) \\

\Rightarrow c^{2} \equiv 0(\bmod 8) \Rightarrow 4 \mid c .

\end{array}

$$

Notice,

$$

(a+b)^{2}-c^{2}>a^{2}+b^{2}-c^{2}=2018>0 \text {. }

$$

Therefore, $a+b-c>0$.

Since $a+b-c$ is even, thus, $a+b-c \geqslant 2$.

And $1+1009^{2}-1008^{2}=2018$, at this time,

$$

a+b-c=1+1009-1008=2 \text {. }

$$

Thus, the minimum value of $a+b-c$ is 2.

(1) If $c=4$, then

$$

\begin{array}{l}

(a+b)^{2}>a^{2}+b^{2}=c^{2}+2018>45^{2} \\

\Rightarrow a+b \geqslant 46 ;

\end{array}

$$

If $a+b=46$, then

$$

a^{2}+b^{2}=a^{2}+(46-a)^{2}=2034

$$

$\Rightarrow a^{2}-46 a+41=0$, this equation has no integer solutions;

If $a+b=48$, then

$$

\begin{array}{l}

a^{2}+b^{2}=a^{2}+(48-a)^{2}=2034 \\

\Rightarrow a^{2}-48 a+135=0 \Rightarrow a=3 \text { or } 45 \\

\Rightarrow a+b+c=52 ;

\end{array}

$$

If $a+b \geqslant 50$, then $a+b+c \geqslant 54$.

(2) If $c \geqslant 8$, similarly, $a+b \geqslant 46$, hence

$$

a+b+c \geqslant 46+8=54 \text {. }

$$

In summary, the minimum value of $a+b-c$ is $2$, and the minimum value of $a+b+c$ is 52.

| 3.25

|

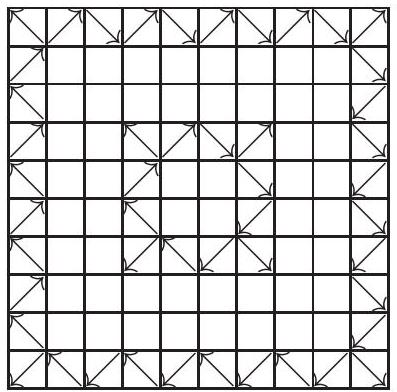

The Dingoberry Farm is a 10 mile by 10 mile square, broken up into 1 mile by 1 mile patches. Each patch is farmed either by Farmer Keith or by Farmer Ann. Whenever Ann farms a patch, she also farms all the patches due west of it and all the patches due south of it. Ann puts up a scarecrow on each of her patches that is adjacent to exactly two of Keith's patches (and nowhere else). If Ann farms a total of 30 patches, what is the largest number of scarecrows she could put up?

|

7

|

Whenever Ann farms a patch $P$, she also farms all the patches due west of $P$ and due south of $P$. So, the only way she can put a scarecrow on $P$ is if Keith farms the patch immediately north of $P$ and the patch immediately east of $P$, in which case Ann cannot farm any of the patches due north of $P$ or due east of $P$. That is, Ann can only put a scarecrow on $P$ if it is the easternmost patch she farms in its east-west row, and the northernmost in its north-south column. In particular, all of her scarecrow patches are in different rows and columns. Suppose that she puts up $n$ scarecrows. The farthest south of these must be in the 10th row or above, so she farms at least 1 patch in that column; the second-farthest south must be in the 9th row above, so she farms at least 2 patches in that column; the third-farthest south must be in the 8th row or above, so she farms at least 3 patches in that column, and so forth, for a total of at least $$1+2+\cdots+n=n(n+1) / 2$$ patches. If Ann farms a total of $30<8 \cdot 9 / 2$ patches, then we have $n<8$. On the other hand, $n=7$ scarecrows are possible, as shown.

| 7

|

Let $x_{1}=y_{1}=x_{2}=y_{2}=1$, then for $n \geq 3$ let $x_{n}=x_{n-1} y_{n-2}+x_{n-2} y_{n-1}$ and $y_{n}=y_{n-1} y_{n-2}- x_{n-1} x_{n-2}$. What are the last two digits of $\left|x_{2012}\right|$ ?

|

84

|

Let $z_{n}=y_{n}+x_{n} i$. Then the recursion implies that: $$\begin{aligned} & z_{1}=z_{2}=1+i \\ & z_{n}=z_{n-1} z_{n-2} \end{aligned}$$ This implies that $$z_{n}=\left(z_{1}\right)^{F_{n}}$$ where $F_{n}$ is the $n^{\text {th }}$ Fibonacci number $\left(F_{1}=F_{2}=1\right)$. So, $z_{2012}=(1+i)^{F_{2012}}$. Notice that $$(1+i)^{2}=2 i$$ Also notice that every third Fibonnaci number is even, and the rest are odd. So: $$z_{2012}=(2 i)^{\frac{F_{2012}-1}{2}}(1+i)$$ Let $m=\frac{F_{2012}-1}{2}$. Since both real and imaginary parts of $1+i$ are 1 , it follows that the last two digits of $\left|x_{2012}\right|$ are simply the last two digits of $2^{m}=2^{\frac{F_{2012}-1}{2}}$. By the Chinese Remainder Theorem, it suffices to evaluate $2^{m}$ modulo 4 and 25 . Clearly, $2^{m}$ is divisible by 4 . To evaluate it modulo 25, it suffices by Euler's Totient theorem to evaluate $m$ modulo 20. To determine $\left(F_{2012}-1\right) / 2$ modulo 4 it suffices to determine $F_{2012}$ modulo 8. The Fibonacci sequence has period 12 modulo 8 , and we find $$\begin{aligned} F_{2012} & \equiv 5 \quad(\bmod 8) \\ m & \equiv 2 \quad(\bmod 4) \end{aligned}$$ $2 * 3 \equiv 1(\bmod 5)$, so $$m \equiv 3 F_{2012}-3 \quad(\bmod 5)$$ The Fibonacci sequence has period 20 modulo 5 , and we find $$m \equiv 4 \quad(\bmod 5)$$ Combining, $$\begin{aligned} m & \equiv 14 \quad(\bmod 20) \\ 2^{m} & \equiv 2^{14}=4096 \equiv 21 \quad(\bmod 25) \\ \left|x_{2012}\right| & \equiv 4 \cdot 21=84 \quad(\bmod 100) \end{aligned}$$

| 7.4

|

In a round-robin tournament, 23 teams participated. Each team played exactly once against all the others. We say that 3 teams have cycled victories if, considering only their games against each other, each of them won exactly once. What is the maximum number of cycled victories that could have occurred during the tournament?

|

506

|

Let's solve the problem more generally for $n$ teams, where $n$ is an odd number. We will represent each team with a point. After a match between two teams, an arrow should point from the losing team to the winning team. (In this context, we can assume that there has never been a tie.)

If the teams $A$, $B$, and $C$ have beaten each other in a cycle, which can happen in two ways, then the triangle $ABC$ is called directed. Otherwise, the triangle is not directed.

Provide an estimate for the number of non-directed triangles.

In every non-directed triangle, there is exactly one vertex such that the team represented by this vertex has beaten the other two. We will count the non-directed triangles according to the "winning" vertex.

Let the teams be represented by the points $A_{1}, A_{2}, \ldots, A_{n}$, and let $d_{i}$ denote the number of wins for $A_{i}$. Since there were a total of $\binom{n}{2}$ matches, $\sum_{i=1}^{n} d_{i}=\frac{n(n-1)}{2}$. Then, $\binom{d_{i}}{2}$ non-directed triangles are associated with the vertex $A_{i}$, since we need to choose two from the teams it has beaten.

Thus, the total number of non-directed triangles is: $\sum_{i=1}^{n}\binom{d_{i}}{2}$.

By the inequality between the arithmetic mean and the quadratic mean:

$$

\begin{gathered}

\sum_{i=1}^{n}\binom{d_{i}}{2}=\frac{1}{2} \sum_{i=1}^{n} d_{i}^{2}-\frac{1}{2} \sum_{i=1}^{n} d_{i}=\frac{1}{2} n \frac{\sum_{i=1}^{n} d_{i}^{2}}{n}-\frac{1}{2} \sum_{i=1}^{n} d_{i} \geq \frac{1}{2} n\left(\frac{\sum_{i=1}^{n} d_{i}}{n}\right)^{2}-\frac{1}{2} \sum_{i=1}^{n} d_{i}= \\

=\frac{1}{2} n\left(\frac{n-1}{2}\right)^{2}-\frac{1}{2} \frac{n(n-1)}{2}=\frac{n^{3}-4 n^{2}+3 n}{8}

\end{gathered}

$$

Can equality hold here? Yes, if we can provide a directed complete graph for which

$$

d_{1}=d_{2}=\cdots=d_{n}=\frac{n-1}{2}

$$

Let $n=2 k+1$. Then one possible construction is as follows:

If $1 \leq i<j \leq 2 k+1$ and $j-i$ is greater than $k$, then $A_{j}$ beat $A_{i}$, otherwise $A_{i}$ beat $A_{j}$. It is easy to verify that in this case,

$$

d_{1}=d_{2}=\cdots=d_{n}=\frac{n-1}{2}

$$

Since there are $\binom{n}{3}$ triangles in total, the number of directed triangles in our case is

$$

\binom{n}{3}-\frac{n^{3}-4 n^{2}+3 n}{8}=\frac{n(n-1)(n-2)}{6}-\frac{n^{3}-4 n^{2}+3 n}{8}=\frac{n^{3}-n}{24}

$$